Comprehensive Guide to Human Papillomavirus (HPV): Understanding, Prevention, and Management

In a past article, we shared information about HPV, providing a broad overview of its health implications. However, as our clientele continues to expand, with an increasing number presenting immune dysfunction and positive infection diagnoses, it became evident that we needed to offer more comprehensive information.

Let’s go back to basics.

Abstract:

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a prevalent infection with significant implications for public health worldwide. This comprehensive guide aims to provide a thorough understanding of HPV, including its epidemiology, transmission, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, medical management and strategies, and holistic approaches to prevention and management. By addressing these aspects comprehensively, this guide seeks to empower you with the knowledge needed to effectively address HPV-related diseases and improve overall health outcomes.

HPV overview

HPV and cervical cancer

Overview of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and its Significance

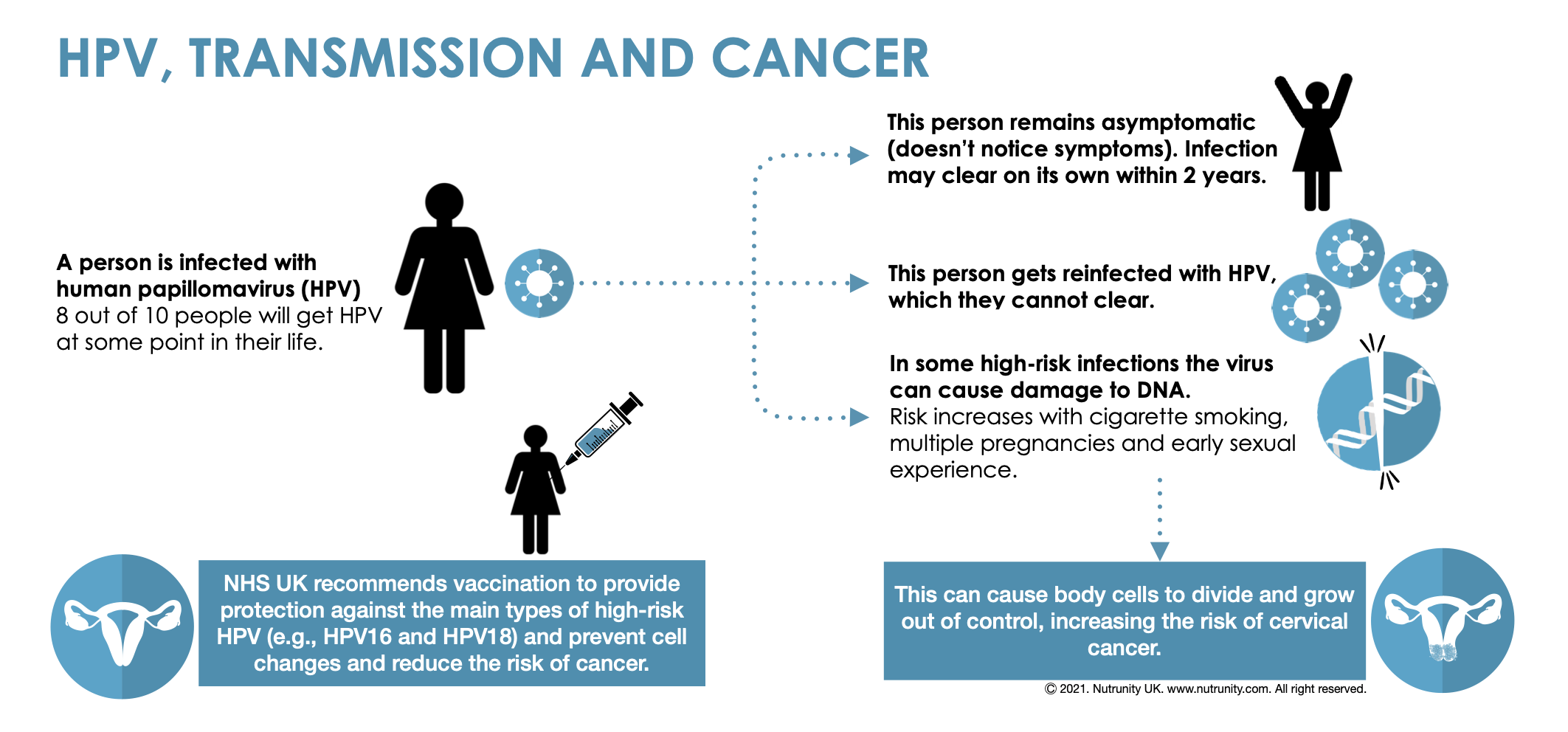

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a common viral infection affecting the skin and mucous membranes. It is the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection (STI) globally, with millions of new cases diagnosed each year. HPV can cause a range of clinical manifestations, from benign warts to potentially life-threatening cancers. Understanding the significance of HPV is crucial for effective prevention, diagnosis, and management of associated diseases.

1. Epidemiology

HPV is highly prevalent worldwide, with an estimated 80% of sexually active individuals contracting the virus at some point in their lives.

Certain populations, such as adolescents, young adults, and immunocompromised individuals, are at higher risk of HPV infection.

High-risk sexual behaviours, lack of access to healthcare services, and socioeconomic factors contribute to the spread of HPV in vulnerable populations.

2. Modes of Transmission

HPV is primarily transmitted through intimate skin-to-skin contact, including sexual activity. Genital-to-genital, genital-to-oral, or genital-to-anal contact can facilitate transmission.

Non-sexual transmission routes, such as vertical transmission from mother to child during childbirth or through fomites like shared towels, also exist.

Factors such as the presence of genital warts, viral load, and immune status influence the likelihood of HPV transmission.

3. Clinical Manifestations

HPV infections can present with various clinical manifestations, including:

Genital Warts: Caused by low-risk HPV types, these warts may appear as single or clustered lesions on the genital, anal, or oral mucosa.

Precancerous Lesions: Persistent infection with high-risk HPV types can lead to precancerous changes in cervical, anal, and other mucosal tissues.

HPV-Associated Cancers: High-risk HPV types are implicated in the development of cervical, anal, penile, vaginal, vulvar, and oropharyngeal cancers.

4. Diagnosis of HPV

Screening tests, such as the Pap smear and HPV testing, are used to detect HPV-related abnormalities in cervical cells.

Colposcopy and biopsy may be performed to further evaluate abnormal findings detected on screening tests.

HPV testing can also be used to identify high-risk HPV types in other anatomical sites, such as the anus, penis, or oropharynx.

5. Medical Management

Treatment options for HPV-related conditions vary depending on the clinical presentation:

Genital Warts: Topical medications, cryotherapy, surgical excision, or laser therapy may be used to remove warts.

Precancerous Lesions: Procedures such as loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) or cone biopsy may be performed to remove abnormal tissue and prevent progression to cancer.

HPV-Associated Cancers: Multidisciplinary treatment approaches, including surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy, are used to manage HPV-related cancers.

Importance of Comprehensive Understanding and Management of HPV

HPV infections are so prevalent that a comprehensive understanding and management approach to HPV are crucial for several reasons:

1. Prevention of HPV-Related Diseases.

Comprehensive knowledge of HPV transmission routes, risk factors, and preventive measures can empower individuals to make informed decisions regarding their sexual health.

Effective prevention strategies, such as safe sexual practices, can reduce the incidence of HPV infections and associated diseases, including genital warts and various cancers.

2. Early Detection and Treatment of HPV-Associated Abnormalities.

Screening programs, such as Pap smears and HPV testing, play a critical role in detecting precancerous lesions and early-stage cancers caused by HPV.

Early detection allows for timely intervention and treatment, preventing the progression of HPV-associated abnormalities to invasive cancer and improving patient outcomes.

Epidemiology

Prevalence and Incidence Rates Globally:

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide, with millions of new cases reported annually.

Prevalence rates vary by geographic region, age group, and population demographics.

Studies estimate that approximately 80% of sexually active individuals will acquire an HPV infection at some point in their lives.

Persistent infections with high-risk HPV types can lead to the development of cervical and other HPV-associated cancers.

High-Risk Populations and Associated Risk Factors:

Certain populations are at increased risk of HPV infection and related complications:

Adolescents and Young Adults: HPV infections are most commonly acquired during adolescence and early adulthood, coinciding with the onset of sexual activity.

Immunocompromised Individuals: People with weakened immune systems, such as those living with HIV/AIDS or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, are at higher risk of HPV-related diseases.

Sexually Active Individuals: Factors such as the number of sexual partners, early age of sexual debut, and lack of condom use increase the risk of HPV transmission.

Marginalised and Underserved Communities: Socioeconomic factors, including limited access to healthcare services, education, and preventive interventions, contribute to disparities in HPV prevalence and outcomes.

Transmission

HPV transmission occurs through various routes, including sexual, vertical, and non-sexual means. Understanding these modes of transmission and the factors influencing transmission dynamics is crucial for implementing effective prevention strategies. Modes of Transmission:

1. Sexual Transmission.

HPV is primarily transmitted through intimate skin-to-skin contact during sexual activity, including vaginal, anal, and oral sex.

Genital-to-genital contact facilitates the transfer of HPV between partners, leading to infection of the genital and anal mucosa.

Factors such as the number of sexual partners, frequency of sexual activity, and condom use influence the risk of HPV transmission.

2. Vertical Transmission.

Vertical transmission refers to the transmission of HPV from mother to child during childbirth.

Infants born to mothers with genital HPV infections may acquire the virus as they pass through the birth canal, leading to the development of juvenile-onset respiratory papillomatosis (JORRP) or genital warts in the child.

3. Non-Sexual Routes.

HPV can also be transmitted through non-sexual means, such as direct or indirect contact with infected skin or mucous membranes.

Shared items like towels, clothing, or personal hygiene products may serve as fomites for HPV transmission, particularly in settings with poor hygiene practices.

Factors Influencing Transmission Dynamics

1. Presence of Genital Warts.

Individuals with visible genital warts are more likely to transmit HPV to their sexual partners due to the higher viral load present in warts.

Genital warts serve as a reservoir for HPV transmission and can facilitate the spread of the virus during sexual contact.

2. Viral Load and Infectiousness:

The viral load of HPV in genital secretions correlates with the likelihood of transmission.

Individuals with high viral loads, particularly those with persistent HPV infections, are more infectious and may have a higher risk of transmitting the virus to their partners.

3. Immune Status.

Host immune factors play a crucial role in determining HPV transmission dynamics.

Immunocompromised individuals, such as those living with HIV/AIDS or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, are at higher risk of persistent HPV infections and may be more likely to transmit the virus to others.

4. Behavioral Factors.

Sexual behaviours, including the number of sexual partners, frequency of sexual activity, and condom use, influence the risk of HPV transmission.

Risky sexual behaviours, such as unprotected sex or engaging in sexual activity at a young age, increase the likelihood of HPV acquisition and transmission.

Clinical Manifestations

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infections can manifest in various clinical presentations, ranging from benign warts to potentially life-threatening cancers. Understanding these manifestations is essential for timely diagnosis and appropriate management.

1. Genital Warts.

Types: Genital warts, also known as condylomata acuminata, are caused by low-risk HPV types, particularly HPV 6 and HPV 11.

Presentation: Genital warts typically appear as small, flesh-coloured or pink bumps or clusters on the genital, anal, or perineal area.

Management:

Topical Treatments: Podofilox, imiquimod, and sinecatechins are commonly used topical medications to treat genital warts by inducing local immune responses or disrupting wart tissue.

Ablative Therapies: Cryotherapy, electrocautery, or laser therapy may be recommended to remove warts by destroying affected tissue.

Surgical Excision: Large or resistant warts may require surgical removal under local anaesthesia.

2. Precancerous Lesions.

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN): Refers to abnormal changes in cervical cells caused by HPV infection, ranging from mild dysplasia (CIN 1) to severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ (CIN 3).

Presentation: CIN lesions may be detected during cervical cancer screening tests, such as Pap smears or colposcopy, and appear as abnormal areas of the cervical epithelium.

Management: Treatment options include surveillance, excisional procedures (e.g., loop electrosurgical excision procedure [LEEP]), or ablative therapies (e.g., cryotherapy) to remove abnormal tissue and prevent progression to invasive cancer.

Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia (AIN): Represents precancerous changes in the anal epithelium associated with HPV infection, particularly in individuals with a history of anal intercourse or HIV infection.

Presentation: AIN lesions may be asymptomatic or present with anal discomfort, bleeding, or pruritus.

Management: Similar to CIN, treatment may involve surveillance, excisional procedures, or topical therapies (e.g., imiquimod) to remove or suppress abnormal anal lesions.

3. HPV-Associated Cancers.

Cervical Cancer: HPV infection, particularly with high-risk types such as HPV 16 and HPV 18, is a major risk factor for cervical cancer development.

Presentation: Symptoms may include abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, or vaginal discharge, but early-stage cervical cancer is often asymptomatic.

Management: Treatment options depend on the stage of cancer and may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of modalities.

Anal, Penile, Vaginal, and Vulvar Cancers: HPV infection is also implicated in the development of cancers affecting the anal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar regions.

Presentation: Symptoms vary depending on the site of the cancer but may include pain, bleeding, or changes in bowel or urinary habits.

Management: Treatment involves surgical resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapies tailored to the specific cancer type and stage.

Oropharyngeal Cancer: HPV, particularly HPV 16, is a leading cause of oropharyngeal cancers, affecting the tonsils, base of the tongue, and other areas of the throat.

Presentation: Symptoms may include sore throat, difficulty swallowing, or a persistent lump in the neck.

Management: Treatment options include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of modalities, with a focus on preserving speech and swallowing function.

Diagnosis

HPV infections are diagnosed through various methods, including screening tests, HPV testing, colposcopy, and biopsy. These diagnostic tools are important to detect HPV-related abnormalities and guide appropriate management strategies.

1. Pap Smear: Screening for Cervical Abnormalities

Purpose: Pap smear, also known as cervical cytology or Pap test, is a screening test used to detect abnormal cervical cells that may indicate HPV infection or precancerous changes.

Procedure: During a Pap smear, a healthcare provider collects cells from the cervix using a small spatula or brush. The cells are then examined under a microscope for any abnormalities.

Indications: Pap smears are typically recommended for individuals with a cervix, starting at age 21 and performed every 3-5 years, depending on age and risk factors.

Interpretation: Results of a Pap smear may include normal, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), or carcinoma.

2. HPV Testing: Detection of High-Risk HPV Types

Purpose: HPV testing is used to detect the presence of high-risk HPV types, particularly HPV 16 and HPV 18, which are associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer.

Procedure: HPV testing involves collecting cells from the cervix, similar to a Pap smear. The cells are then tested for the presence of HPV DNA using molecular techniques, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or nucleic acid hybridization.

Indications: HPV testing may be performed alone or in conjunction with a Pap smear as part of cervical cancer screening. It is often recommended for individuals aged 30 and older, or as follow-up testing for abnormal Pap smear results.

Interpretation: A positive HPV test indicates the presence of high-risk HPV types in the cervix, which may warrant further evaluation with colposcopy and biopsy.

3. Colposcopy and Biopsy: Further Evaluation of Abnormal Findings

Purpose: Colposcopy is a diagnostic procedure used to visually examine the cervix, vagina, and vulva for any abnormalities, such as suspicious lesions or areas of dysplasia.

Procedure: During colposcopy, a colposcope (a magnifying instrument) is used to visualize the cervix and identify abnormal areas. If suspicious lesions are identified, a biopsy may be performed to obtain tissue samples for pathological evaluation.

Indications: Colposcopy is indicated for individuals with abnormal Pap smear results, positive HPV tests, or visible lesions on visual inspection.

Interpretation: Pathological evaluation of biopsy specimens helps determine the presence and severity of cervical dysplasia or neoplasia, guiding further management decisions.

Medical Management of HPV-Related Conditions

HPV infections can lead to various clinical manifestations, including genital warts, precancerous lesions, and HPV-associated cancers. Effective medical management aims to treat existing lesions, prevent disease progression, and reduce the risk of complications.

1. Treatment of Genital Warts.

Topical Medications:

Imiquimod: Immune response modifier cream applied to warts stimulates the body's immune system to attack HPV-infected cells.

Podophyllotoxin: Topical solution or gel applied directly to warts inhibits cell division in infected tissues.

Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) or Bichloroacetic Acid (BCA): Chemical agents applied to warts to destroy infected tissue.

Ablative Therapies:

Cryotherapy: Freezing of warts using liquid nitrogen, causing cell destruction and subsequent wart removal (in the same way verrucas are often removed).

Electrosurgery: Application of high-frequency electrical current to burn off warts.

Laser Therapy: Precise removal of warts using laser energy to destroy infected tissue.

Surgical Interventions: include excision (surgical removal of warts using a scalpel or scissors under local anaesthesia) or cauterisation (destruction of warts using heat or chemicals to prevent recurrence).

Management of Precancerous Lesions

Loop Electrosurgical Excision Procedure (LEEP): Electrosurgical technique to remove abnormal cervical tissue (e.g., CIN) using a wire loop heated by electric current. Precise removal of affected tissue under local anaesthesia, minimising damage to surrounding healthy tissue.

Cone Biopsy (Conisation): Surgical procedure to remove a cone-shaped wedge of abnormal cervical tissue for pathological evaluation. Allows for accurate diagnosis and treatment of high-grade cervical dysplasia or carcinoma in situ.

Other Excisional Procedures:

Cold Knife Conisation: Surgical removal of abnormal cervical tissue using a scalpel.

Laser Conisation: Precise removal of abnormal tissue using laser energy.

3. Multidisciplinary Cancer Care.

Surgical Interventions:

Cervical Cancer: Radical hysterectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, or trachelectomy may be performed for early-stage cervical cancer.

Anal Cancer: Wide local excision, abdominoperineal resection, or colostomy may be indicated for anal cancer treatment.

Radiation Therapy: External beam radiation or brachytherapy may be used alone or in combination with surgery for locally advanced or unresectable HPV-associated cancers.

Systemic Therapies:

Chemotherapy: Cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens are commonly used as adjuvant or palliative treatment for HPV-associated cancers.

Immunotherapy: Checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab or nivolumab, may be used to support the immune response against HPV-infected cancer cells.

HPV Vaccination

Since it is part of the modern medicine approach, HPV vaccination needs to be discussed in this article. Vaccination is a primary prevention strategy aimed at reducing the incidence of HPV infections and associated diseases, including genital warts and HPV-related cancers.

Routine HPV vaccination is recommended for all adolescents aged 11-12 years, with catch-up vaccination recommended for individuals aged 13-26 years who have not been previously vaccinated.

Vaccine Efficacy, Safety, and Dosing Schedules:

1. Efficacy: Clinical trials have demonstrated high efficacy rates for HPV vaccines in preventing HPV infection, genital warts, and HPV-related precancerous lesions. Long-term follow-up studies have confirmed sustained protection against HPV-related diseases for at least 10 years post-vaccination.

2. Safety: HPV vaccines are generally well-tolerated. Common side effects include pain at the injection site, redness, swelling, headache, and mild fever. According to doctors, serious adverse events are rare.

3. Dosing Schedules: HPV vaccines are administered via intramuscular injection in two or three doses depending on the vaccine.

Common Side effects: Pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site are the most common side effects reported after HPV vaccination. The discomfort is typically mild to moderate and resolves within a few days. They also include:

Headache

Fatigue

Fever is more common after the first dose and tends to occur within a day or two of vaccination.

Nausea

Dizziness

Muscle or Joint Pain

Allergic Reactions. In some cases, individuals may experience allergic reactions to components of the HPV vaccine, such as yeast or aluminium, including hives, swelling of the face or throat, difficulty breathing, or rapid heartbeat. Allergic reactions require immediate medical attention.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS). While rare, there have been reports of GBS occurring after HPV vaccination. GBS is a neurological disorder characterised by muscle weakness, tingling sensations, and paralysis. The association between HPV vaccination and GBS is still being studied.

Blood Clots. Vaccines work by stimulating the body's immune system to produce an immune response against specific pathogens and may lead to the activation of platelets (small blood cells involved in clotting) and the formation of blood clots. Additionally, vaccines contain adjuvants or other components that can lead to abnormal blood clotting.

Holistic Approaches and Lifestyle Modifications

In addition to medical interventions, holistic approaches and lifestyle modifications play a significant role in supporting overall health and well-being, including the prevention and management of HPV-related conditions. These approaches encompass nutritional support, smoking cessation, stress reduction techniques, and other lifestyle modifications aimed at optimising health outcomes.

1. Nutritional Support.

Dietary Recommendations:

Consuming a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans and pulses, lean proteins, and healthy fats provides essential nutrients, antioxidants, and phytochemicals that support immune function and overall health. Adequate intake of vitamins A, C, D, E, and folate, as well as minerals like magnesium, zinc and selenium, is important for immune health and may help manage HPV infections.

Supplementation:

In some cases, supplementation with specific nutrients or vitamins may be beneficial, especially for individuals with nutrient deficiencies or compromised immune function. Indole-3-carbinol is one compound promising for CIN.[13]

HPV also tends to be tightly joined with oestrogen dominance syndrome. Rectifying hormonal imbalance may also be key in reducing the onset of HPV-related cancer.[17] Several factors can contribute to the development of estrogen dominance syndrome:

Hormonal Imbalance: Oestrogen dominance can occur when there is an imbalance between estrogen and progesterone production or metabolism. This imbalance can result from various factors, including irregular menstrual cycles, perimenopause, or conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or ovarian cysts.

Excess Oestrogen Production: Certain factors can lead to increased estrogen production in the body. These may include obesity, as adipose tissue (fat cells) produce oestrogen as a warning call; excessive alcohol consumption; exposure to environmental estrogens (xenoestrogens) found in plastics, pesticides, and other synthetic chemicals; and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or oral contraceptives containing high levels of estrogen.

Impaired Oestrogen Metabolism: Proper estrogen metabolism is essential for maintaining hormonal balance. Dysfunction in the liver, where oestrogen is metabolised and detoxified, can lead to impaired estrogen metabolism and accumulation of estrogen metabolites. Factors such as poor liver function, excessive alcohol intake, and nutrient deficiencies (e.g., vitamins B6, B12, folate, and magnesium) can contribute to impaired oestrogen metabolism. Cells also rely on detoxification pathways to detoxify no longer-needed oestrogen.

Progesterone Deficiency: Progesterone plays a crucial role in balancing oestrogen levels in the body. Insufficient progesterone production or decreased sensitivity to progesterone's effects can contribute to estrogen dominance. This may occur during perimenopause, when progesterone levels decline while oestrogen levels remain elevated, or due to chronic stress, which can disrupt the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and suppress progesterone production.

Stress: Chronic stress can impact hormonal balance by increasing cortisol levels and disrupting the production and function of sex hormones like oestrogen and progesterone. Elevated cortisol levels can lead to adrenal fatigue, which may further exacerbate oestrogen dominance.

Diet and Lifestyle Factors can influence oestrogen metabolism and hormone balance. A diet high in refined carbohydrates, sugar, and processed foods can contribute to insulin resistance and promote oestrogen dominance. Additionally, sedentary lifestyle habits and lack of regular exercise may impair hormone metabolism and contribute to weight gain, further exacerbating oestrogen dominance.

Environmental Factors: Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in the environment, such as bisphenol A (BPA), phthalates, parabens, and pesticides, can mimic estrogen in the body and disrupt hormonal balance. These chemicals are found in various consumer products, including plastics, personal care products, and food packaging.

Genetic Predisposition: Some individuals may have a genetic predisposition to oestrogen dominance due to variations in genes involved in oestrogen metabolism and hormone receptor sensitivity.

2. Smoking and Vaping.

Smoking is a well-established risk factor for HPV-related cancers, including cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers. Tobacco smoke contains carcinogens that can damage DNA, impair immune function, and promote the progression of HPV-related lesions to invasive cancer.

Quitting smoking can significantly improve treatment outcomes for individuals with HPV-related cancers. Smoking cessation reduces the risk of disease recurrence, improves response to therapy, and enhances overall survival rates.

3. Stress Reduction Techniques.

Mindfulness Meditation: Mindfulness meditation involves focusing your attention on the present moment, promoting relaxation, stress reduction, and emotional well-being. Mindfulness practices can help individuals cope with the psychological impact of HPV-related conditions, reduce anxiety, and enhance resilience.

Yoga combines physical postures, breathing exercises, and meditation techniques to improve flexibility, strength, and mental clarity. Regular practice has been associated with reduced stress, improved mood, and enhanced quality of life for individuals facing health challenges.

Relaxation Strategies: Engaging in relaxation techniques such as deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, or guided imagery can elicit the body's relaxation response, counteract stress, and promote emotional balance.

4. Regular Physical Activity.

Engaging in regular physical activity promotes overall health and strengthens the immune system, which plays a crucial role in fighting off HPV infections and preventing HPV-related diseases. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise per week, along with muscle-strengthening activities on two or more days per week.

5. Immune-supporting Herbs and Supplements.

Certain herbs and supplements have immune-supporting properties that may provide support to the body's defence against HPV infections. Examples include echinacea, astragalus, garlic, and probiotics. However, they may interact with medications or have contraindications. Never supplement unsupervised.

6. Holistic Therapies.

Explore holistic therapies such as acupuncture, acupressure, naturopathy, or traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to promote overall well-being and support immune function. These modalities focus on restoring balance and harmony within the body, which may complement conventional medical treatments for HPV-related conditions.

These modalities also operate on the principle that the body possesses innate healing abilities and that health is maintained through the balance and harmony of various internal systems.

Acupuncture Involves the insertion of thin needles into specific points on the body, known as acupoints, to stimulate energy flow (Qi) and restore balance within the body's meridian system.

Benefits: Acupuncture may help alleviate pain, reduce inflammation, and improve immune function by regulating the body's neuroendocrine and immune responses. It can also support stress reduction and promote relaxation, which are beneficial for overall health and immune function.

Acupressure is similar to acupuncture but involves applying pressure to acupoints using the fingers, thumbs, or specialised tools, rather than needles.

Benefits: Acupressure can help relieve tension, promote circulation, and stimulate the body's natural healing processes. It may also support immune function by reducing stress, improving sleep quality, and enhancing overall well-being.

Naturopathic Medicine is a holistic approach to healthcare that emphasises the body's inherent ability to heal itself through natural therapies, lifestyle modifications, and prevention.

Benefits: Naturopathic treatments may include dietary counselling, herbal medicine, nutritional supplementation, hydrotherapy, and lifestyle interventions tailored to individual health needs. These therapies can help support immune function, optimise nutritional status, and address underlying imbalances contributing to HPV-related conditions.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). TCM is a comprehensive system of medicine that includes acupuncture, herbal medicine, dietary therapy, massage (Tui Na), and movement exercises (Qigong). It is based on the concepts of Yin and Yang, Qi (vital energy), and the Five Elements.

Benefits: TCM approaches aim to restore harmony and balance within the body, address root imbalances, and strengthen the body's resistance to disease. Herbal medicine formulas may be prescribed to support immune function, resolve dampness or phlegm accumulation, and clear heat or toxins associated with HPV infections.

Benefits of Holistic Therapies for HPV-related Conditions:

Support Immune Function: Holistic therapies can help strengthen the body's immune response to HPV infections, promoting viral clearance and reducing the risk of disease progression.

Alleviate Symptoms: Acupuncture, acupressure, and herbal medicine may help alleviate symptoms such as pain, inflammation, genital warts, and menstrual irregularities associated with HPV-related conditions.

Improve Well-being: These modalities can support emotional well-being, reduce stress, and improve the quality of life for individuals navigating the physical and emotional challenges of HPV infections and associated conditions.

7. Emotional Support and Counseling.

Dealing with a diagnosis of HPV or HPV-related conditions can be emotionally challenging. Seek out emotional support from friends, family members, support groups, or mental health professionals who can provide guidance, empathy, and coping strategies to navigate the emotional aspects of the journey.

8. Environmental and Lifestyle Factors.

Pay attention to environmental and lifestyle factors that may influence HPV risk and progression. Minimise exposure to environmental toxins, such as air pollution or chemicals in personal care products, and adopt healthy lifestyle habits, such as adequate sleep, hydration, and healthy sun exposure.

9. Regular Screening and Follow-up.

Stay proactive with regular screening tests, such as Pap smears and HPV testing, as recommended by healthcare providers. Early detection of HPV-related abnormalities allows for timely intervention and treatment, improving outcomes and reducing the risk of disease progression.

Conclusion

This comprehensive guide explored various aspects of HPV prevention and management, highlighting the importance of a holistic approach to addressing this prevalent viral infection. Here's a recap of the key points discussed:

Understanding HPV: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) is a common sexually transmitted infection that can lead to genital warts, precancerous lesions, and HPV-related cancers, including cervical, anal, penile, vaginal, vulvar, and oropharyngeal cancers.

Comprehensive Prevention Strategies: Effective prevention of HPV infections and associated diseases requires a multifaceted approach, which includes vaccination, regular screening, practising safe sex, and promoting healthy lifestyle habits.

Early Detection and Screening: Routine screening tests, such as Pap smears and HPV testing, are essential for detecting HPV-related abnormalities early, enabling timely intervention and treatment to prevent disease progression.

Medical Management: Treatment options for HPV-related conditions include topical medications, ablative therapies, surgical interventions, and multidisciplinary cancer care, tailored to individual needs and disease severity.

Holistic Approaches: Holistic therapies, such as acupuncture, acupressure, naturopathy, and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), can complement conventional medical treatments by promoting overall well-being, supporting immune function, and addressing underlying imbalances contributing to HPV-related conditions.

Lifestyle Modifications: Lifestyle factors, including nutrition, smoking cessation, stress reduction techniques, regular physical activity, and emotional support, play a crucial role in supporting immune function and optimizing health outcomes for individuals with HPV-related conditions.

Importance of Comprehensive Approaches

A comprehensive approach to HPV prevention and management is essential for addressing the complex challenges posed by this widespread viral infection. By integrating medical interventions, holistic therapies, and lifestyle modifications, healthcare providers can offer personalised care plans that address the unique needs of each individual.

References:

CDC. (2024). https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/anogenital-warts.htm

NHS. (2024). Genital warts. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/genital-warts

NHS. (2023). HPV vaccine. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/vaccinations/hpv-vaccine

WHO. (2024). Human papillomavirus and cancer. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papilloma-virus-and-cancer

National Cancer Institute. (2023). HPV and Cancer. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-and-cancer

IARC Working Group. (2007). IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Human Papillomaviruses. Lyon (FR): International Agency for Research on Cancer. (IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, No. 90.) 1, Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321770/

ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). (2023). Available from: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XWX.pdf.

Adams, M. Borysiewicz, L. Fiander, A. et al. (2001). Clinical studies of human papilloma vaccines in pre-invasive and invasive cancer. Vaccine. 19(17-19), pp. 2549-2556. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00488-6

Ahdieh, L. Muñoz, A. Vlahov, D. et al. (2000). Cervical neoplasia and repeated positivity of human papillomavirus infection in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive and -seronegative women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 151(12), pp. 1148-1157. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010165

Alam, M. Caldwell, JB. Eliezri, YD. (2003). Human papillomavirus-associated digital squamous cell carcinoma: Literature review and report of 21 new cases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 48(3), pp. 385-393. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.184

Ames, BN. Wakimoto, P. (2002). Are vitamin and mineral deficiencies a major cancer risk? Nature Reviews Cancer. 2(9), pp. 694-704. doi:10.1038/nrc886

Barton, SE. Maddox, PH. Jenkins, D. et al. (1988). Effect of cigarette smoking on cervical epithelial immunity: A mechanism for neoplastic change? Lancet. 2(8612), pp. 652-654. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90469-2

Bauman, NM. Smith, RJ. (1996). Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 43(6), pp. 1385-1401. doi:10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70524-1

Bell, MC. Crowley-Nowick, P. Bradlow, HL. et al. (2000). Placebo-controlled trial of indole-3-carbinol in the treatment of CIN. Gynecologic Oncology. 78(2), pp. 123-129. doi:10.1006/gyno.2000.5847

Bernard, HU. (2002). Gene expression of genital human papillomaviruses and considerations on potential antiviral approaches. Antiviral Therapy. 7(4), pp. 219-237.

Bjørge, T. Engeland, A. Luostarinen, T. et al. (2002). Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for anal and perianal skin cancer in a prospective study. British Journal of Cancer. 87(1), pp. 61-64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600350. Erratum in: Br J Cancer. 2004. 91(6), 1226.

Bodaghi, S. Yamanegi, K. Xiao, SY. et al. (2005). Colorectal papillomavirus infection in patients with colorectal cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 11(8), pp. 2862-2867. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1680

Brake, T. Lambert, PF. (2005). Estrogen contributes to the onset, persistence, and malignant progression of cervical cancer in a human papillomavirus-transgenic mouse model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102(7), pp. 2490-2495. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409883102

Bruni, L. Albero, G. Rowley, J. et al. (2023). Global and regional estimates of genital human papillomavirus prevalence among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health. 11(9), e1345-e1362. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00305-4

Bruni, L. Diaz, M. Castellsagué, X. et al. (2010). Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 202(12), pp. 1789-1799. doi:10.1086/657321

Chesson, HW. Dunne, EF. Hariri, S. et al. (2014). The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 41(11), pp. 660-664. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000193

Clifford, GM. Tully, S. Franceschi, S. (2017). Carcinogenicity of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Types in HIV-Positive Women: A Meta-Analysis From HPV Infection to Cervical Cancer. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 64(9), pp. 1228–1235, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix135

de Martel, C. Georges, D. Bray, F. et al. (2020). Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Global Health. 8(2), e180-e190. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30488-7

de Sanjosé, S. Diaz, M. Castellsagué, X. et al. (2007). Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: A meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Disease. 7(7), pp. 453-459. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5

Ferlay, J. Laversanne, M. Ervik, M. et al. (2024). Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Tomorrow. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow

Houlihan, CF. Larke, NL. Watson-Jones, D. et al. (2012). Human papillomavirus infection and increased risk of HIV acquisition. A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 26(17), pp. 2211-2222. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328358d908

Kechagias, KS. Kalliala, I. Bowden, SJ. et al. (2022). Role of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on HPV infection and recurrence of HPV related disease after local surgical treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis BMJ . 378, e070135. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-070135

Li, X. Gao, C. YANG, Yu. et al. (2013). Systematic review with meta-analysis: The association between human papillomavirus infection and oesophageal cancer. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. doi:10.1111/apt.12574

Liang, Y. Chen, M. Qin, L. et al. (2019). A meta-analysis of the relationship between vaginal microecology, human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Infect Agents Cancer. 14, 29. doi:10.1186/s13027-019-0243-8

Rodríguez, AC. Schiffman, M. Herrero, R. et al. (2008). Proyecto Epidemiológico Guanacaste Group. Rapid clearance of human papillomavirus and implications for clinical focus on persistent infections. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 100(7), pp. 513-517. doi:10.1093/jnci/djn044

Sabeena, S. Bhat, PV. Kamath, V. et al. (2017). Community-based prevalence of genital human papillomavirus (HPV) infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 18(1), pp. 145-154. doi:10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.1.145

Schiffman, M. Doorbar, J. Wentzensen, N. et al. (2016). Carcinogenic human papillomavirus infection. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2, 16086. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.86

Shoja, Z. Farahmand, M. Hosseini, N. et al. (2019). A Meta-Analysis on human papillomavirus type distribution among women with cervical neoplasia in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region. Intervirology. 62(3-4), pp. 101–111. doi:10.1159/000502824

Winer, RL. Hughes, JP. Feng, Q. et al. (2011). Early natural history of incident, type-specific human papillomavirus infections in newly sexually active young women. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 20(4), pp. 699-707. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1108