Comprehensive Guide to Ankylosing Spondylitis: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Management

What Is Ankylosing Spondylitis?

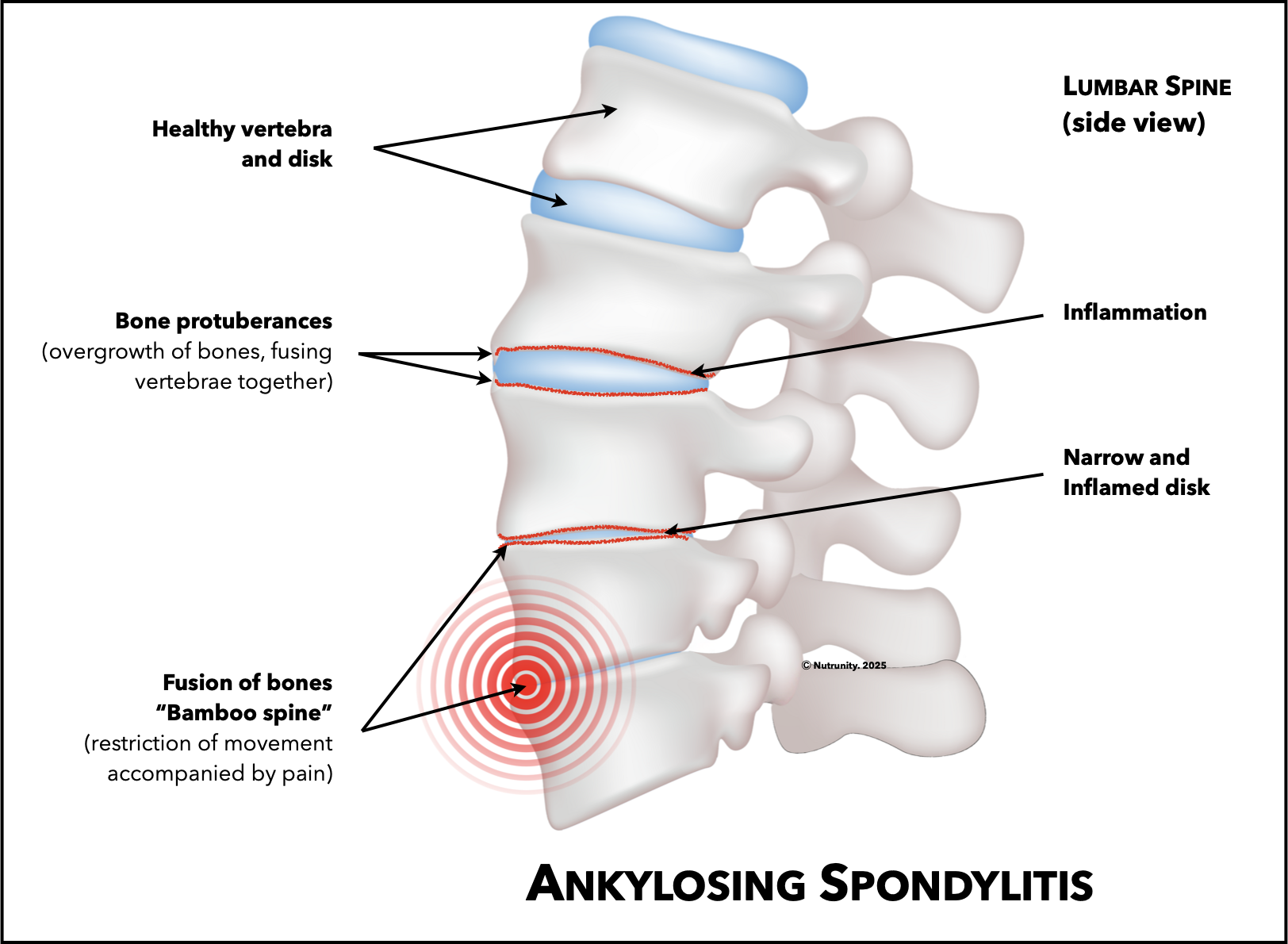

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), or axial spondyloarthritis, is an immune-mediated, chronic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints, tendons, and ligaments. This progressive form of rheumatic disease (Spondyloarthropathy) can cause pain, stiffness, and, in severe cases, fusion of the vertebrae, leading to a rigid and less flexible spine, known as Ankylosis.

While AS predominantly targets the spine, other joints, such as the hips, shoulders, knees, and even ribs (which can make breathing difficult), may also be affected. The condition can also extend beyond the musculoskeletal system, causing eye inflammation (uveitis), skin disorders (psoriasis), or gastrointestinal issues (inflammatory bowel disease).

Although there is currently no cure for ankylosing spondylitis, early diagnosis and targeted treatment can significantly improve quality of life and slow disease progression. Traditional treatments focus on managing symptoms, but naturopathic medicine offers a more comprehensive approach that addresses root causes and provides long-term relief.

Recent data suggest that patients wait 6-to-8 years to be diagnosed properly.[1.1.] Prevalence has increased in the last 30 years, particularly in women and people aged over 60 years. AS may affect over 1% of the global population.

Schematic illustration of Ankylosing Spondylitis, showing normal vertebra and disk, and disease progression

Early Signs and Symptoms of Ankylosing Spondylitis

The symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis can range from mild to severe, often fluctuating between flare-ups and periods of remission. Early signs include persistent lower back and hip pain. This pain typically lasts for more than three months. Stiffness, especially in the morning or after periods of inactivity, is another common symptom. Fatigue is another symptom reported by most patients.

Common symptoms include:

Chronic lower back pain and stiffness, especially after periods of rest or inactivity

Reduced flexibility in the spine over time

Pain and swelling in other joints, including the hips, knees, and shoulders

Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath due to rib cage or chest wall stiffness.

Eye inflammation (uveitis), causing redness, pain, and sensitivity to light

Fatigue and generalised weakness

Skin changes, including rashes or lesions (commonly linked to psoriasis)

Gastrointestinal issues, including abdominal pain and diarrhoea, particularly in those with co-existing inflammatory bowel disease

Loss of appetite or unexplained weight loss.

Main symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis

Progression and Complications

Without proper intervention, AS can progress, causing severe complications such as:

Spinal fusion, leading to a hunched posture (Kyphosis).

Reduced lung capacity due to rib fusion

Inflammation in other joints, eyes, or the cardiovascular system

Chronic pain and reduced mobility

Light sensitivity and vision problems

Nerve damage

Spine fractures (4 times greater risk in patients with AS than in the general population, largely because of the combination of rigidity and osteoporosis).

Systemic rheumatic disorder causing inflammation of skeletal bones, joints and ligaments, causing deformity of the spine (kyphosis)

Causes and Risk Factors for Ankylosing Spondylitis

Like other autoimmune diseases, AS develops through complex interactions between genetic background and environmental factors. The cause of the disease is unclear, but clinical studies suggest its prevalence is approximately two to three times greater in men than in women. It is most heavily related to genetics, infection, and trauma. According to statistics, the disease is heritable by more than 90% and is mainly related to HLA-B27 genetic factors.[1-3] The most prevalent subtypes in AS are HLA-B2705 (Caucasian populations), HLA-B2704 (Chinese populations), and HLA-B2702 (Mediterranean populations). By contrast, two subtypes, HLA-B2706 and HLA-B2709, seem unrelated.[4]

Even as the most emphasised genetic factor, HLA-B27 contributes only about 20% to AS heritability. This demonstrates that many other key factors play a decisive role in the onset and progression of the disease.

AS is usually associated with chronic inflammation involving dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, NK cells, and adaptive immune cells, which produce various innate cytokines (signalling proteins that help control inflammation in the body).

Microbial infection may trigger the host's innate immune system and AS development. Specific strains of bacteria have been implicated. Some scientists hypothesise that Klebsiella pneumonia, in particular, influences AS development indirectly through interplay with HLA-B27.

Researchers also found a correlation between chronic periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis and SA.[5] This may be because rheumatic diseases and chronic periodontitis share pathogenic factors, including dysfunctional inflammatory mechanisms and an imbalance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Other infections, including fungal, Candida albicans, bacterial (chlamydia, Klebsiella pneumoniae), viral (HPV, HIV), and mycoplasma (Mycoplasma pneumonia), may also play a role.[6] Immune organs, such as the tonsils, are involved in allergen tolerance, contributing to autoimmune arthritis, including AS. Spondylitis might also aggravate tonsillitis, creating a vicious cycle.[7] Of all infections, chest infections are the most common cause, followed by herpes zoster (23.7%), gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary tract infections.[8] Interestingly, common treatment options, mainly with high doses and longer duration of treatment, increased the risk of infection in patients with AS, mostly respiratory tract or ear, nose, and throat infections.[9]

This is very important because infections can be a trigger for ankylosing spondylitis flare-ups, and people with AS have an increased risk of infections and death from infections, particularly respiratory tract infections.

There may also be a hormonal component and an impaired hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in AS patients, suggesting that the endocrine system is involved in the aetiology of AS.[10] Chronic stress, unresolved trauma, anxiety disorders and sleep problems are known to dysregulate the HPA axis. Low oestrogen is implicated in osteoporosis and may be a marker of AS, especially during menses. Interestingly, pregnancy may also play a role in the onset of AS.

Damage to the nervous system can result in issues like urinary incontinence, loss of bowel control, and sexual dysfunction.

Sex hormones influence immune processes. This may explain why males are more likely to have SA than females and why females may not respond to certain treatments. Furthermore, sex hormones influence other physiological processes, such as pain transmission (testosterone increases the pain threshold), explaining why female patients experience higher levels of pain, especially during the menstrual cycle. Besides the influence of hormones, they also have more pain receptors and different expressions of these receptors. This could explain the overall higher pain sensitivity in women compared with men, which might contribute to higher pain scores reported for patient questionnaires by women with rheumatic diseases.[11]

“An interesting study on genetic expression in AS revealed that 1522 unique genes were expressed in men and 291 genes in women compared with healthy controls.”

Several studies have reported an association between a high BMI and a lower TNF inhibitor (TNFi) treatment response, which means that obesity, an inflammatory condition, may also prevent effective resolution.[13,14]

Nutrient deficiencies, particularly immune-supporting vitamins and minerals like vitamin D, selenium and zinc, may be implicated in SA. Low levels are strongly correlated with disease severity (and mortality) and are common in patients with AS.[15] They may also have low haemoglobin (Hb) and iron (Fe), which is more prevalent in female patients. Studies reveal that 1/3 of patients are also deficient in B12.[16]

Conversely, inflammatory diets, such as the SAD diet and ultra-processed diets, which are poor in dietary fibre, marine omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, and selenium, play a key role in the progression and severity of the disease. Therefore, the most important aspect of treatment alongside increased physical activity is a nutrient-dense diet.[17]

— Genetic and Environmental Triggers

While the exact cause of ankylosing spondylitis remains unclear, it is widely accepted that both genetic and environmental factors play a role. The HLA-B27 gene is a significant genetic marker, increasing susceptibility to AS. However, carrying the gene does not guarantee the development of the condition, suggesting that environmental factors like infections or lifestyle may also play a major role.

— Associated Conditions

Ankylosing spondylitis often coexists with other inflammatory conditions, such as Crohn's disease and psoriasis. These diseases share immune dysregulation pathways, which can potentially worsen AS symptoms.

— Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers

While genetics lay the groundwork, environmental factors — including stress, poor diet, and sedentary lifestyles — can exacerbate inflammation and trigger AS symptoms.

Sleep problems can also exacerbate symptoms as the body struggles to rest, heal and repair.

Risk Factors

Family history: A close relative with ankylosing spondylitis increases your risk.

Age: Symptoms typically appear between the ages of 15 and 45, with a mean age onset of 37 in males.

Sex: Men are more likely to develop ankylosing spondylitis than women, though women may experience subtler symptoms.

Associated conditions: Psoriasis, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis can increase your likelihood of developing AS.

How Is Ankylosing Spondylitis Diagnosed?

— Medical History and Physical Examination

A thorough evaluation begins with a detailed medical and family history, focusing on pain duration, nature, and related symptoms like fatigue or eye inflammation. A physical exam assesses spinal flexibility, posture, and ribcage movement.

Your doctor may ask about your medical and family history, including questions such as:

How long have you had pain?

Where is the pain?

What makes the pain better or worse?

Is there any family history of back pain, joint pain, or arthritis?

A physical exam may include:

Examining your joints, including spine, pelvis, heels, and chest.

Watching how you move and bend in different directions, checking for flexibility.

Asking you to breathe deeply to check for rib stiffness and inflammation.

— Imaging Techniques

X-rays: To detect changes in the spine or sacroiliac joints, although these may only become visible in advanced stages.

MRI Scans: Useful for identifying early inflammation and structural damage before it appears on x-rays.

Bone protuberances may fracture, irritating nerves and leading to pain that imaging may not pick up.

— Laboratory Tests

Currently, there is no test to diagnose ankylosing spondylitis. However, your doctor may recommend a blood test to check for the HLA-B27 gene commonly found in individuals with AS. While having the HLA-B27 gene doesn’t guarantee you will develop ankylosing spondylitis, it can provide valuable information for diagnosis. Additionally, your doctor may order lab tests to assess blood counts and inflammation markers, which can help evaluate the extent of the disease (e.g., elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)).

Treatment Options

Although ankylosing spondylitis has no cure, effective management strategies can help keep symptoms under control, preserve mobility, and improve quality of life.

Your doctor will work with you to manage the condition effectively. Treatment aims to:

Relieve symptoms.

Maintain proper posture, flexibility, and strength.

Halt or slow the progression of the disease.

Most treatment plans involve a combination of medication and physical therapy. In severe cases, surgery may be necessary to repair joint damage.

— Medications

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), especially selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2, are first-line treatments for patients with active AS to relieve pain and reduce inflammation.

Biologic Therapies, such as TNF inhibitors or IL-17 inhibitors, to target immune pathways and halt disease progression.

JAK Inhibitors. A new class of drugs to treat chronic inflammatory disorders by blocking the action of enzymes that cause inflammation for those unresponsive to traditional biologics.

Corticosteroid Injections: Provide short-term relief in inflamed joints. Studies have shown that partly because of the increased risks of osteoporosis, hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance, long-term treatment with systemic glucocorticoids is contraindicated.[4,18]

— Physical Therapy and Exercise

Your doctor may suggest physical therapy to:

Relieve pain.

Strengthen back and neck muscles.

Enhance core and abdominal strength, as these muscles support your back.

Improve posture.

Maintain and enhance joint flexibility.

A physical therapist can guide you on optimal sleeping positions and design an exercise program tailored to your needs. Since symptoms often worsen with inactivity or prolonged rest, staying active and exercising regularly is essential.

Recommended activities include:

Stretching and strengthening exercises for back and core muscles.

Low-impact activities, such as swimming or yoga, to enhance joint mobility and reduce pain.

Maintaining good posture is essential, even during sleep. Opt for a firm mattress and avoid using thick pillows. Sleep with your legs straight instead of curled. Additionally, ensure you stand and sit upright, avoiding stooping or slouching.

— Surgical Interventions

In advanced cases with severe joint damage, surgical options like joint replacement or spinal correction may be considered.

Lifestyle Changes to Manage AS

Research shows that individuals actively involved in their care experience less pain, require fewer doctor visits, and enjoy a higher quality of life. Self-care empowers you to manage your condition and improve your overall health.

— Self-Care Strategies

Educate Yourself: Learn about the disease and available treatments to make informed decisions

Effective Communication: Work closely with your healthcare team

Seek Support: Connect with others to cope with the physical, emotional, and mental challenges of ankylosing spondylitis.

Participating in your care can build confidence in managing daily activities, allowing you to lead a full, active, and independent life.

— Activities

1. Exercise

Regular exercise helps maintain muscle strength, joint mobility, and flexibility. Low-impact activities like water exercises may also be recommended. Always consult your healthcare provider before starting any program. Benefits of exercise include:

Improved sleep

Pain reduction

A positive mindset

Maintaining a healthy weight.

2. Posture

Good posture is critical to avoiding complications associated with ankylosing spondylitis. Your doctor or physical therapist can provide exercises and tips for improving and maintaining posture.

3. Support and Assistive Devices

A cane or walker can enhance mobility, provide stability, and reduce pain. Adaptive tools for picking up items can help manage spine stiffness.

4. Monitor Symptoms

Keep track of any changes or new symptoms. Understanding symptom patterns helps you and your doctor better manage flares and pain.

5. Mental Health Support

If you feel anxious, depressed, or isolated, speak with a mental health professional. Keep open communication with family and friends, and consider joining a support group for additional encouragement.

— Stay Active

Engage in regular physical activity to minimise stiffness and maintain flexibility. Always consult a healthcare provider before starting an exercise programme.

— Practise Good Posture

Focus on posture-correcting exercises to prevent complications like kyphosis (hunchback).

— Quit Smoking

Smoking worsens symptoms, accelerates disease progression, and reduces the effectiveness of treatment.

— Manage Stress

Managing stress can make living with AS easier. Incorporate stress-relieving practices like mindfulness, deep breathing, and journaling to improve emotional well-being. You may also want to try Qi gong. Listening to calming music can also provide relief before bed.

Managing stress can make living with AS easier. Consider these strategies:

Practice relaxation techniques like deep breathing, meditation, or calming music.

Try movement-based programs such as yoga, tai chi or Gi gong.

— Healthy Eating

A nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory diet rich in fruits, vegetables, omega-3 fatty acids, and whole grains can support overall health. Maintaining a healthy weight also reduces strain on joints.

A low-starch diet may help with AS by reducing the growth of pathogenic microbes in the gut. Foods to avoid include those high in fat, salt, and sugar, as well as processed foods, dairy products, alcohol, caffeine, and artificial sweeteners. Foods to eat include those rich in antioxidants, such as fruits and vegetables, and those rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as salmon, flax seeds, and certain nuts.

References:

1.1.

Seo, MR. Baek, HL. Yoon, HH. et al. (2015). Delayed diagnosis is linked to worse outcomes and unfavourable treatment responses in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Clinical Rheumatology. 34, pp. 1397–405.

Slobodin, G. Reyhan, I. Avshovich, N. et al. (2011). Recently diagnosed axial spondyloarthritis: Gender differences and factors related to delay in diagnosis. Clinical Rheumatology. 30, pp. 1075–1080.

Zwolak, R. Suszek, D. Graca, A. et al. (2019). Reasons for diagnostic delays of axial spondyloarthritis. Wiadomości Lekarskie Medical Advances. 72(9 cz 1), pp. 1607–1610.

Redeker, I. Callhoff, J. Hoffmann, F. et al. (2019). Determinants of diagnostic delay in axial spondyloarthritis: An analysis based on linked claims and patient-reported survey data. Rheumatology (Oxford). 58, pp. 1634–1638.

1. Wright, GC. Kaine, J. Deodhar, A. (2020). Understanding differences between men and women with axial spondyloarthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 50(4), pp. 687–694. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.05.005

2. Sieper, J. Poddubnyy, D. (2017). Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 390(10089), pp. 73–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4

3. Reveille, JD. (2006). The genetic basis of ankylosing spondylitis. Current Opinions in Rheumatology. 18(4), pp. 332–341. doi:10.1097/01.bor.0000231899.81677.04.

4. Zhu, W. He, X. Cheng, K. et al. (2019). Ankylosing spondylitis: Etiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Bone Research. 7, 22. doi:10.1038/s41413-019-0057-8

5. Keller, J. Kang, JH. Lin, HC. (2013). Association between ankylosing spondylitis and chronic periodontitis: A population-based study. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 65(1), pp. 167-73. doi:10.1002/art.37746

6. Wei, JC. Chou, MC. Huang, JY. et al. (2020). The association between candida infection and ankylosing spondylitis: A population-based matched cohort study. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 36, pp. 2063–2069. doi:10.1080/03007995.2020.1838460

7. Zhang, X. Sun, Z. Zhou, A. et al. (2021). Association between infections and risk of ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Immunology. 12, 768741. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.768741

8. Ko, KM. Moon SJ. (2022). Incidence and risk of overall infections in patients with ankylosing spondylitis receiving biologic therapies: A real-world prospective observational study using Kobio registry. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 81,786.

9. Séauve, M. Auréal, M. Laplane, S. et al. (2024). Risk of infections in psoriatic arthritis or axial spondyloarthritis patients treated with targeted therapies: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Joint Bone Spine. 91(3), 105673. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2023.105673

10. Gooren. LJ. Giltay, EJ. van Schaardenburg, D. et al. (2000). Gonadal and adrenal sex steroids in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 26(4), pp. 969-987. doi:10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70179-4

11. Rusman, T. van Bentum, RE. van der Horst-Bruinsma, IE. (2020). Sex and gender differences in axial spondyloarthritis: Myths and truths. Rheumatology (Oxford). 59(Suppl4): iv38-iv46. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keaa543

12. Gracey, E. Yao, Y. Green, B. et al. (2016). Sexual dimorphism in the Th17 signature of ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 68(3), pp. 679-689. doi:10.1002/art.39464

13. Aloush, V. Ablin, JN. Reitblat, T. et al. (2007). Fibromyalgia in women with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology International. 27(9), pp. 865-868. doi:10.1007/s00296-007-0344-3

14. Zeboulon, N. Dougados, M. Gossec, L. (2008). Prevalence and characteristics of uveitis in the spondyloarthropathies: a systematic literature review. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 67(7), pp. 955-959. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.075754

15. Ben-Shabat, N. Watad, A. Shabat, A. et al. (2020). Low vitamin D levels predict mortality in ankylosing spondylitis patients: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Nutrients. 12(5), 1400. doi:10.3390/nu12051400

16. Triggianese, P. Caso, F. Della Morte, D. et al. (2022). Micronutrient deficiencies in patients with spondylarthritis: The potential immunometabolic crosstalk in disease phenotype. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 26(6), pp. 2025-2035. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202203_28351

17. Hulander, E. Zverkova Sandstrom, T. Backman Renman, J. et al. (2023). Patients with ankylosing spondylitis have an impaired dietary intake - preliminary results from patients in Sweden. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 82, pp. 331-332.

6. Haibel, H. Fendler, C. Listing, J. et al. (2014). Efficacy of oral prednisolone in active ankylosing spondylitis: Results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled short-term trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 73(1), pp. 243-246. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203055

7.