Uterine Fibroids: A Holistic Approach

Fibroids are non-cancerous growths that develop in or around the uterus. The growths are made up of muscle and fibrous tissue and vary in size.

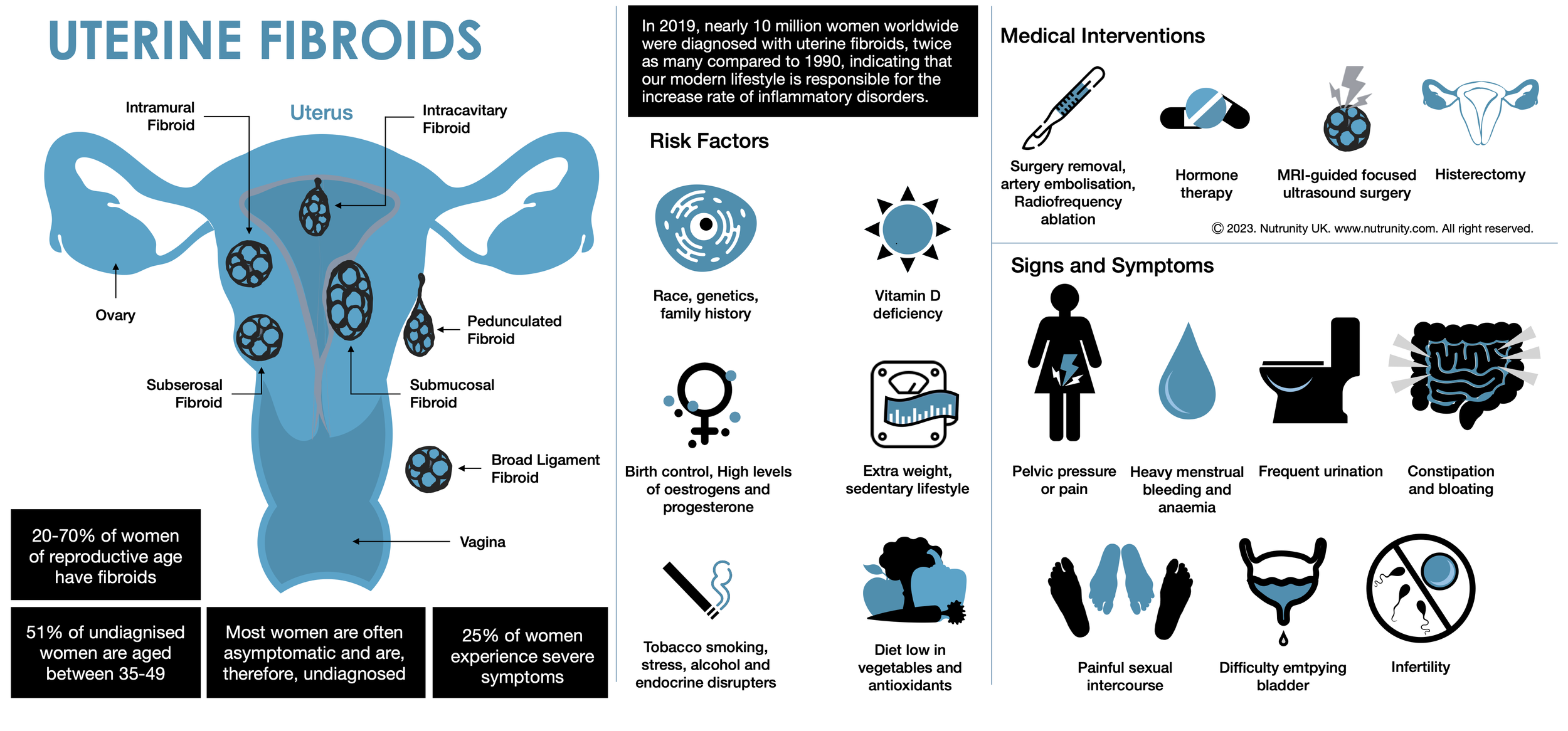

Uterine fibroids (leiomyomas or myomas) represent the most prevalent benign tumours in women. Research suggests a lifetime prevalence ranging from 70% to 80%, depending on the studied population and diagnostic methods.[1,2] Notably, studies highlight a two to threefold increased risk of uterine fibroids in Black women compared to other racial populations. The risk increases with early onset of menses, late menopause, nulliparity (a woman who has not been pregnant yet), and obesity.

In the early stages, fibroids may often go undetected in routine physical examinations and be asymptomatic.[3] However, these benign tumours can lead to a spectrum of issues, including heavy menstrual bleeding and abnormal uterine bleeding, and consequent anaemia, pelvic pain, infertility, and recurrent pregnancy loss.[4]

Uterine fibroids are not cancer, and they rarely turn into cancer. They are not linked with a higher risk of other types of cancer in the uterus either.

Fibroids vary in number and size. You can have a single fibroid or several, and some can grow to the size of a grapefruit or be so big they can distort the inside and the outside of the uterus. In extreme cases, some fibroids grow large enough to fill the pelvis or stomach area and make a person look pregnant.

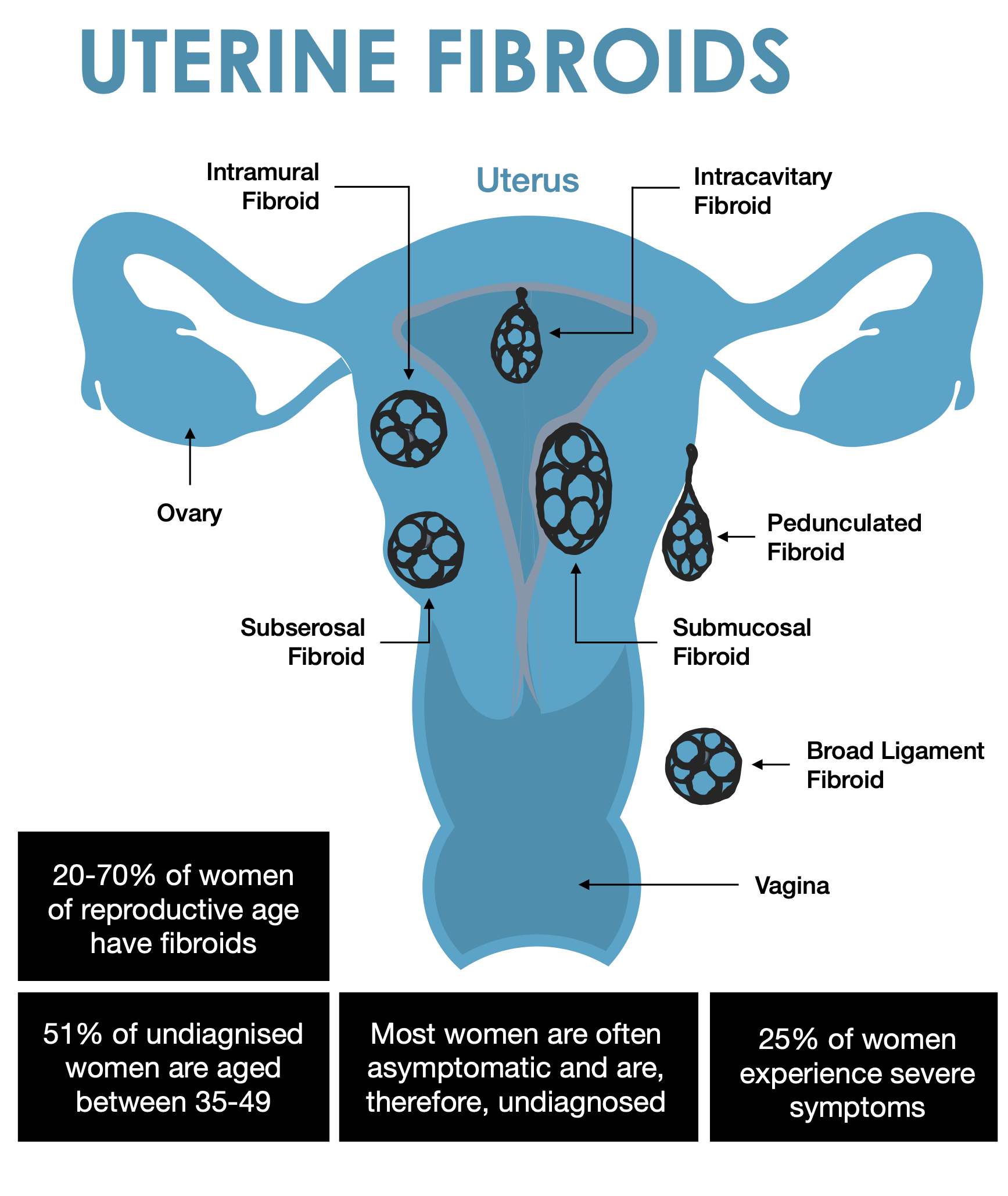

Types of uterine fibroids

Depending on where they’re located and how they attach, uterine fibroids are called:

Intramural fibroids are embedded into the muscular wall of your uterus — the most common type.

Submucosal fibroids grow under the inner lining of your uterus.

Subserosal fibroids grow under the lining of the outer surface of your uterus. They can become quite large and grow into your pelvis.

Pedunculated fibroids. The least common type, these fibroids appear like hanging fruits.

Risk Factors

Age (older women are at higher risk than younger women)

Black women[4a,4b]

Contraceptive pill[4c]

Obesity

Family history of uterine fibroids

High blood pressure

No history of pregnancy

Vitamin D deficiency

Food additive consumption[5a]

Use of soybean milk.[5a,5b]

While some risk factors like race, age, and family history may not be modifiable, lifestyle factors, such as physical activity, chronic stress, dietary habits, and smoking, can play a crucial role in influencing the risk of developing fibroids.[5,6]

Signs and Symptoms

Heavy menstrual bleeding or painful periods.

Longer or more frequent periods.

Pelvic pressure or pain.

Frequent urination, incomplete bladder emptying, or difficulty urinating (as the fibroid(s) apply pressure on the bladder.

Increased abdominal distention (enlargement).

Constipation.

Pain in the stomach area or lower back, or pain during sex.

Ongoing tiredness and weakness (typical symptoms of anaemia).

Medical approach

Surgery

Radiologic therapies

Common holistic interventions

Addressing gut health,

Improving detoxification and elimination,

Normalising insulin levels,

Exercising daily, and

A balanced diet (e.g., Mediterranean Diet)

Impact of Nutrition on Fibroid Risk

Several nutrients and dietary habits have been implicated in the development of uterine fibroids, such as low intake of fruits and vegetables, vitamin D deficiency, and increased exposure to toxicants in foods (including additives and non-intentionally added substances and contaminants. e.g., phthalates and acrylamide).[7]

A case-controlled study using premenopausal women highlights the protective effect of higher vegetable and fruit consumption, while a high body mass index (BMI) emerges as a significant risk factor.[8]

The relationship between visceral fat and uterine fibroid development was explored in a 2019 case-control study. The findings suggested that increased body fat, particularly abdominal visceral fat, may enhance the risk of uterine fibroids and could serve as an indicator for screening high-risk groups. The study highlights the importance of nutrition guidance and lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, in preventing uterine fibroid development.

It is also important to note that chronic stress, HPA axis dysregulation (hyperactivated stress response), chronic lack of sleep, and poor gut health (due to stress and resulting in hyperactivity of the immune system, also a stressor), all contribute to increased abdominal visceral fat.

Chronic Stress and Hormone Disruption

Hormones have a widespread effect on our mental, physical, and emotional health. Hormonal dysregulation can play a critical role in imbalances occurring throughout the body.

Research suggests that sex hormones and their metabolites influence not only reproductive functions but also brain areas governing mood, behaviour, and cognitive abilities.[9] Most importantly, the dominant effect of stress hormones can impact all other hormones, creating a self-feeding cycle: Stress can both predispose individuals to and precipitate hormonal imbalances.[10,11]

Surprisingly, various aspects of our lifestyle can throw hormones off balance. Nutrition, exposure to air pollution, and chronic stress are among the main culprits.[10, 12-15] These findings highlight a crucial link between our daily choices and hormonal balance.

Factors Predisposing Women to Fibroids

Despite their high prevalence (uterine fibroids affect up to 70-80% of women), fibroids often go undiagnosed. In addition, the consensus on evidence-based treatment strategies is still unclear, contributing to challenges in managing this condition effectively.

Genetic Influences and Oestrogen Responsiveness

Fibroids are acknowledged for their oestrogen responsiveness, with both genetic factors and ovarian hormone exposure playing crucial roles in their development. Studies highlight racial disparities, with Black women experiencing larger and more frequent fibroids at an earlier age. The consequential heavy bleeding often leads to anaemia, fatigue, and pain, impacting the quality of life for affected women.

Risk Factors

The underlying causes of fibroids remain incompletely understood, with non-modifiable risk factors such as age, race, genetic predisposition, and family history taking precedence. Also, modern medicine, in its quest for a pill-for-an-ailment, is categorically unequipped to provide a solution at this present time and so the condition is poorly understood.

Modifiable lifestyle factors, including increased blood pressure, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and low vitamin D levels, emerge as potential contributors. Chronic inflammation also emerges as a possible factor in fibroid formation. And so, a holistic approach is vital.

Environmental Exposures and Fibroid Development

Environmental toxicants, including cosmetic chemicals, polluted drinking water, air pollution and indoor pollution, are implicated in fibroid development. Longitudinal studies demonstrate a correlation between high air pollution exposure and increased fibroid risk. Additionally, heavy metals and endocrine-disrupting chemicals contribute to the complex interplay of environmental factors in fibroid aetiology.[16]

A Holistic Approach

The management of uterine fibroids requires a multifaceted and holistic approach that extends beyond addressing immediate symptoms. It is essential to consider hormonal imbalances, gut health, inflammation, detoxification, blood sugar regulation, insulin stability, and reduction of endocrine-disrupting chemical exposure.

“Restoring hormonal balance remains crucial even after successful fibroid treatment.”

Gut Health

The intricate relationship between gut health and fibroids is gaining recognition in contemporary medical research. An imbalanced gut microbiome may contribute to chronic inflammation, potentially exacerbating fibroid symptoms.

Integrating dietary strategies, such as incorporating fibre-rich foods and probiotics, holds promise in improving the gut environment and positively influencing fibroid outcomes.

Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is increasingly recognised as a contributing factor in fibroid formation. Addressing inflammation not only alleviates symptoms but may also impede the progression of fibroids. Anti-inflammatory dietary patterns, coupled with targeted nutritional supplements, present viable strategies to mitigate the inflammatory milieu associated with fibroids.

Detoxification

Toxic exposures, both environmental and endogenous, can contribute to fibroid development. Detoxification plays a crucial role in eliminating accumulated toxins from the body, reducing the burden on organs involved in hormone metabolism.

Incorporating liver-supportive foods, hydration, and strategic supplementation supports the body's natural detoxification processes, fostering a healthier internal environment and cellular health.

Blood Sugar Regulation and Insulin Stability

The intricate interplay between blood sugar regulation, insulin stability, and fibroid dynamics is key in fibroid management. Elevated insulin levels and insulin resistance may contribute to the growth of fibroids. Implementing dietary measures to stabilise blood sugar levels, such as adopting a low-glycemic diet, emerges as a fundamental aspect of a holistic fibroid management plan.

Stress management and daily physical activities must also be included in treatment.[17]

Reduction of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical Exposure

Environmental exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals represent a modifiable risk factor in fibroid development. Strategies to reduce exposure to these chemicals include choosing organic products, minimising the use of plastics, and advocating for clean air (use air-filtering systems and anti-pollution plants) and water (filter your water and ban plastic bottled water).

Sustaining Hormonal Balance

The journey doesn't end with successful fibroid protocols. Sustaining hormonal balance post-treatment is imperative to prevent recurrences and enhance overall well-being. Long-term strategies may involve ongoing hormone monitoring, lifestyle modifications, and tailored interventions to address evolving health needs.

Individuals must also take responsibility for their journey to reach a better quality of life.

References

1. Stewart, EA. Cookson, CL. Gandolfo, RA. et al. (2017). Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: A systematic review. BJOG. 124(10), pp. 1501-1512. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14640

2. Giuliani, E. As-Sanie, S. Marsh, EE. (2020). Epidemiology and management of uterine fibroids. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 149(1), pp. 3-9. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13102

3. Sun, K. Xie, Y. Zhao, N. et al. (2019). A case-control study of the relationship between visceral fat and the development of uterine fibroids. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 18(1), pp. 404-410. doi:10.3892/etm.2019.7575

4. Sohn, GS. Cho, S. Kim, YM. et al. (2018). Current medical treatment of uterine fibroids. Obstetrics & Gynecology Science. 61(2), pp. 192-1201. doi:10.5468/ogs.2018.61.2.192

4a. Baird, DD. Dunson, DB. Hill, MC. et al. (2003). High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: Ultrasound evidence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188(1), pp. 100-107. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.99

4b. Faerstein, E. Szklo, M. Rosenshein, N. (2001). Risk factors for uterine leiomyoma: A practice-based case-control study. I. African-American heritage, reproductive history, body size, and smoking. American Journal of Epidemiology. 153(1), pp. 1-10. doi:10.1093/aje/153.1.1

4c. Kwas, K. Nowakowska, A. Fornalczyk, A. et al. (2021). Impact of Contraception on Uterine Fibroids. Medicina (Kaunas). 57(7), 717. doi:10.3390/medicina57070717

5a. Stewart, EA. Cookson, CL. Gandolfo, RA. et al. (2017). Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: A systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 124(10), pp. 1501-1512. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14640

5b. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2018). What are the risk factors for uterine fibroids? Available at: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/uterine/conditioninfo/people-affected. Last accessed: 27th Nov. 2023.

6. Pavone, D. Clemenza, S. Sorbi, F. et al. (2018). Epidemiology and risk factors of uterine fibroids. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 46, pp. 3-11. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.09.004

7. Tinelli A, Vinciguerra M, Malvasi A, Andjic M, Babovic I, Sparic R. Uterine fibroids and diet. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1066. doi:10.3390/ijerph18031066

8. He Y, Zeng Q, Dong S, Qin L, Li G, Wang P. Associations between uterine fibroids and lifestyles including diet, physical activity and stress: a case-control study in China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013;22(1):109-117. doi:10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.1.07

9. Del Río, JP. Alliende, MI. Molina, N. et al. (2018). Steroid hormones and their action in women’s brains: The importance of hormonal balance. Frontiers in Public Health. 6, 141. doi:3389/fpubh.2018.00141

10. Ranabir, S. Reetu, K. (2011). Stress and hormones. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 15(1), pp. 18-22. doi:4103/2230-8210.77573

11. Vita, R. Lapa, D. Trimarchi, F. et al. (2015). Stress triggers the onset and the recurrences of hyperthyroidism in patients with Graves’ disease. Endocrine. 48(1), pp. 254-263. doi:1007/s12020-014-0289-8

12. Köhrle, J. (2015). Selenium and the thyroid. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity. 22(5), pp. 392-401. doi:1097/MED.0000000000000190

13. Jain, RB. (2014). Thyroid function and serum copper, selenium, and zinc in general U.S. population. Biological Trace Element Research. 159(1-3), pp. 87-98. doi:1007/s12011-014-9992-9

14. McCabe, D. Lisy, K. Lockwood, C. et al. (2017). The impact of essential fatty acid, B vitamins, vitamin C, magnesium and zinc supplementation on stress levels in women: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation. 15(2), pp. 402-453. doi:11124/JBISRIR-2016-002965

15. Li, H. Cai, J. Chen, R. et al. (2017). Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of air purification. Circulation. 136(7), pp. 618-627. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026796

16. Mahalingaiah, S. Hart, JE. Laden, F. et al. (2014). Air pollution and risk of uterine leiomyomata. Epidemiology. 25(5), pp. 682-688. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000000126

17. Baird, DD. Dunson, DB. Hill, MC. et al. (2007). Association of physical activity with development of uterine leiomyoma. American Journal of Epidemiology. 165(2), pp. 157-163. doi:10.1093/aje/kwj363