Trauma: Navigating Recovery Through Body and Mind Integration

What is trauma?

Trauma is a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses a wide range of distressing experiences, from acute incidents of violence or abuse to chronic exposure to adversity and neglect. At its core, trauma represents a profound disruption of the individual's sense of safety, security, and well-being, often leaving lasting imprints on their psychological, emotional, and physiological functioning. While trauma is commonly associated with overtly traumatic events such as natural disasters or physical assault, it's essential to recognise that it can also arise from more subtle forms of interpersonal harm, including emotional neglect, invalidation, and betrayal.

Ultimately, trauma is not merely defined by the event itself but by the individual's subjective experience of threat, powerlessness, and distress in response to that event, and any future events that will be recognised as triggers.

Trauma arises from a breakdown in the body's natural response to threat, leading to immobilisation instead of the expected fight or flight reaction. A prime example of this is seen in experiments with 'inescapable shock,' where creatures are subjected to torture without any means of affecting the outcome. This results in physical immobilisation, known as the freeze response, which becomes a conditioned behavioural reaction. Think of it as elephant training. Once chained, they will believe to be prisoners and escape is impossible, even when chains are removed.

“Trauma is not merely defined by the event itself but by the individual’s subjective experience of threat, powerlessness, and distress in response to that event, and any future events that will be recognised as triggers. ”

Interactions between a child and their caregiver lead to lasting physiological and anatomical changes, impacting personality development and various clinical presentations. Negative interactions may induce persistent hyperactivity in the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, profoundly affecting the arousal state of the developing child and influencing behavioural and character development.

Many individuals who have experienced trauma struggle to manage overwhelming emotions effectively, resulting in alexithymia – an inability to identify and interpret physical sensations and muscle activation. This lack of emotional recognition leaves them disconnected from their own needs, hindering their ability to self-care and understand the emotions of others. Consequently, they may react disproportionately to threats or minor irritations, with dissociation and futility becoming recurring themes in their daily lives. They may turn to unhealthy coping mechanisms such as snacking on junk food as a way to numb their emotions or distract themselves from their trauma. However, this reliance on unhealthy snacks only provides temporary relief and can lead to further health issues in the long run.

Impact of trauma on the individual

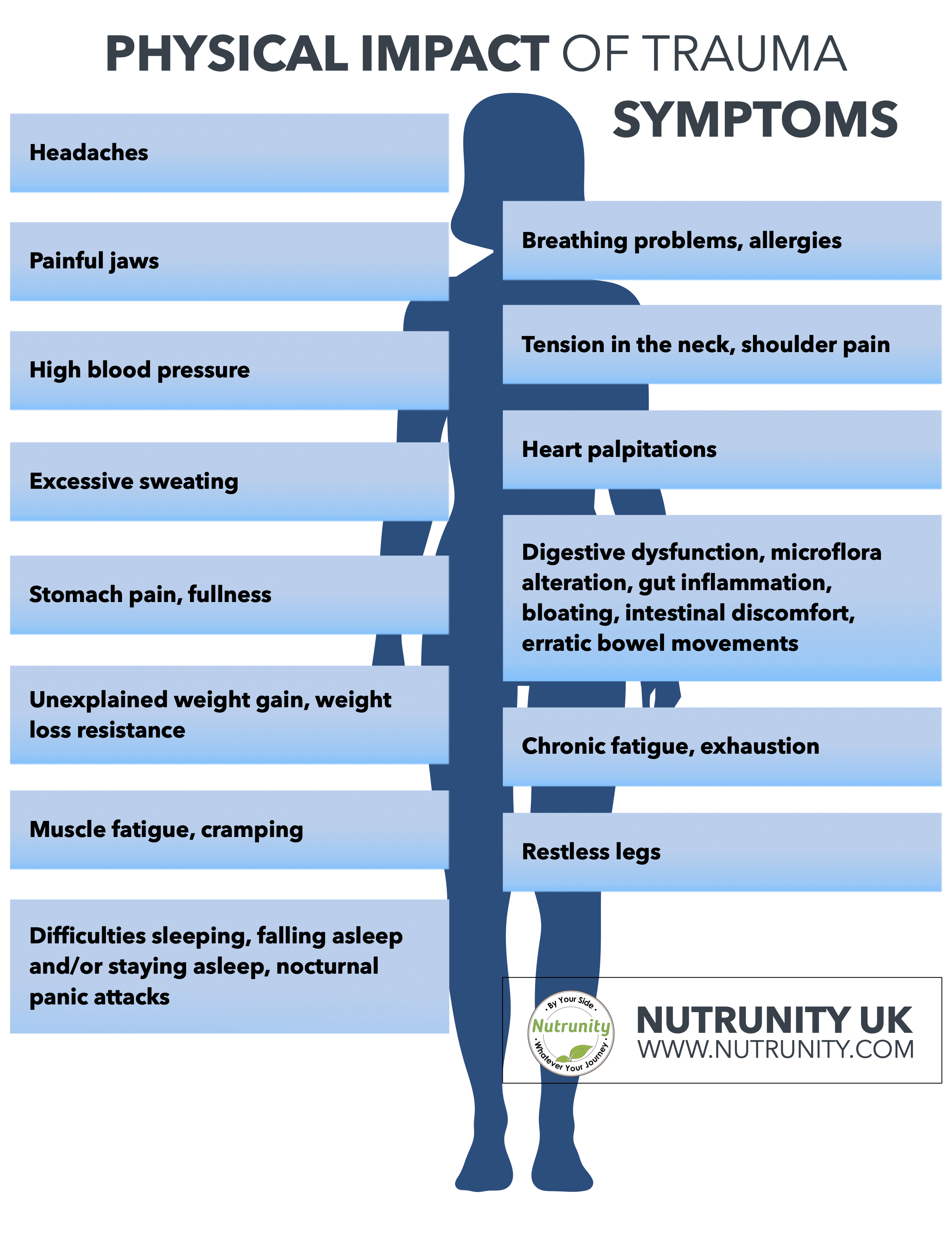

The impact of trauma on individuals can be profound and far-reaching, manifesting in a myriad of psychological, emotional, and physical symptoms. Common psychological sequelae of trauma include symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as intrusive memories, flashbacks, nightmares, and hypervigilance.

Additionally, trauma often undermines individuals' sense of self-worth and identity, leading to feelings of shame, guilt, and self-blame. Emotionally, trauma survivors may struggle with regulating their emotions, experiencing intense mood swings, emotional numbness, or overwhelming feelings of fear and anxiety. Physiologically, trauma can dysregulate the body's stress response systems, contributing to heightened arousal, chronic inflammation, and alterations in neuroendocrine function. These profound disruptions to the individual's internal landscape can significantly impair their overall functioning and quality of life, impacting their relationships, work, and daily activities.

Trauma and adulthood

After experiencing trauma, individuals often continue to navigate life as if the trauma were ongoing, with every new encounter coloured by past experiences. Their nervous system responds differently to the world, with a survivor's energy focused on suppressing inner chaos rather than engaging spontaneously with life. These attempts at control can manifest in physical symptoms, such as autoimmune diseases, underscoring the importance of addressing trauma on all levels — body, mind, and brain.

They may also find it difficult to live authentically according to their core values and beliefs.

Trauma in adulthood and the impact of unresolved trauma

Trauma experienced in adulthood, particularly when left unresolved or unaddressed, can have enduring consequences on individuals' mental, emotional, and physical health.

Unresolved trauma often festers beneath the surface, manifesting in a myriad of maladaptive coping mechanisms and self-destructive behaviours. Individuals may turn to substances such as drugs or alcohol as a means of numbing emotional pain or seek solace in unhealthy relationships or behaviours. These coping strategies, while initially providing a sense of relief, ultimately serve to perpetuate the cycle of trauma, exacerbating feelings of shame, guilt, and isolation. Moreover, unresolved trauma can significantly impair individuals' ability to form secure attachments and navigate intimate relationships, perpetuating patterns of dysfunction and disconnection.

Trauma And The Nervous System

Early exposure to extreme threats, coupled with inadequate caregiving responses, significantly impacts the body's ability to regulate the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems in response to stress. Increased sympathetic activity is common in traumatised individuals, affecting heart rate and metabolic output. Dysfunctions in the parasympathetic system contribute to pathophysiological conditions, including autoimmune disorders, through its influence on digestive and hypoxic responses.

The Dorsal Vagal State

The dorsal vagal state, also known as the freeze response or immobilisation response, represents a primitive survival mechanism activated in response to overwhelming threat or danger. When confronted with a perceived threat that exceeds the individual's capacity to fight or flee, the body enters a state of physiological shutdown, characterised by decreased heart rate, lowered blood pressure, and immobility. This adaptive response, mediated by the dorsal vagus nerve, serves to conserve energy and minimise the risk of further harm in situations where escape is not possible. However, when chronically activated or triggered by past trauma, the dorsal vagal state can become maladaptive, contributing to a range of physical and psychological symptoms, including dissociation, depersonalization, and disconnection from one's internal experience.

The dorsal vagal response is a primitive survival mechanism that the body employs in response to overwhelming danger or threat when neither fight nor flight responses are feasible or effective. This adaptive response is orchestrated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), specifically the parasympathetic branch (PNS), and involves a complex interplay of physiological, neuroendocrine, and neural mechanisms aimed at conserving energy and minimising the risk of further harm.

Mechanisms Involved

Dorsal Vagal Activation:

The immobilisation response is primarily mediated by the dorsal vagus nerve, which is part of the PNS. Activation of the dorsal vagal complex, located in the brainstem, leads to inhibition of sympathetic arousal and dampening of the fight-or-flight response.

Neurotransmitter Regulation:

Neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) play crucial roles in facilitating the immobilisation response. Acetylcholine acts on muscarinic receptors to induce relaxation and reduce heart rate, while GABA inhibits neuronal activity, promoting a state of calmness and tranquillity.

Hormonal Regulation:

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, a key neuroendocrine system involved in stress regulation, is modulated during the immobilisation response. Cortisol levels may decrease, leading to a state of hypoarousal and decreased vigilance — the opposite effect of the stress response or “fight-or-flight.”

Vasovagal Response:

The vasovagal response, characterised by a sudden drop in heart rate and blood pressure, is a hallmark of the immobilisation response. This physiological phenomenon serves to conserve energy and redirect blood flow away from non-essential organs towards vital organs such as the brain and heart.

Brain Activation:

Brain regions implicated in the processing of fear and threat, such as the amygdala and periaqueductal grey (PAG), play critical roles in orchestrating the immobilisation response. Activation of these regions can trigger a cascade of neurochemical events leading to behavioural inhibition and physical immobility.

Purpose of the Immobilisation Response

The immobilisation response serves several adaptive functions aimed at enhancing survival in situations of extreme danger:

Conservation of Energy:

By inducing a state of physical immobility, the body conserves energy that can be redirected towards essential physiological processes necessary for survival, such as maintaining vital organ function and metabolic homeostasis.

Protection from Predators:

Immobilisation renders the individual less conspicuous to predators or threats by minimising movement and reducing the likelihood of detection. In the wild, this strategy can increase the chances of survival by avoiding detection and predation.

Minimisation of Further Harm:

By minimising movement and reducing physiological arousal, the immobilisation response reduces the risk of exacerbating injuries or attracting further aggression from predators or assailants. This protective mechanism allows the individual to "play dead" and escape harm in situations where active defence is futile.

Overall, the immobilisation response represents a fundamental survival strategy employed by the body in response to overwhelming danger or threat, enabling individuals to endure and survive in the face of adversity.

The Dorsal Vagal State in a nutshell

The body initiates the vasovagal response as part of the immobilisation response to conserve energy and prioritise the allocation of resources to vital organs during times of perceived threat or danger. This redirection of blood flow away from non-essential organs towards critical organs like the brain and heart is crucial for maintaining essential physiological functions necessary for survival.

During moments of extreme stress or danger, such as facing a predator or experiencing a traumatic event, the body's primary goal is to ensure the preservation of life. By reducing heart rate and blood pressure, the vasovagal response helps to decrease overall metabolic demand, conserving energy that can be utilised for essential functions like cognitive processing and maintaining cardiac output.

Redirecting blood flow towards vital organs like the brain ensures that these organs receive an adequate oxygen and nutrient supply, enabling them to function optimally despite challenging circumstances. This prioritisation of blood flow helps to sustain cognitive function, alertness, and decision-making abilities, which are essential for assessing and responding to the threat effectively.

Conversely, diverting blood flow away from non-essential organs such as the gastrointestinal tract and skeletal muscles temporarily suppresses functions that are less critical for immediate survival. By reducing blood flow to these areas, the body can minimise energy expenditure on processes like digestion and locomotion, allowing resources to be redirected towards maintaining vital functions and responding to the perceived threat more efficiently.

In the context of a predator attack where physical injury may occur, the redirection of blood flow away from the peripheries towards vital organs serves an additional crucial purpose: reduced bleeding and conserving blood volume.

By constricting blood vessels in the peripheries, particularly in areas where the skin is thinner and more vulnerable to injury, the body limits the amount of blood that can escape from potential wounds caused by predator attacks. This vasoconstriction helps to minimise blood loss, preserving blood volume and ensuring an adequate supply of oxygenated blood to essential organs like the brain and heart.

Furthermore, the release of stress hormones such as adrenaline and noradrenaline during the immobilisation response can contribute to vasoconstriction and blood clotting mechanisms (making the blood thicker), further aiding in the body's ability to control bleeding and maintain cardiovascular stability in the face of injury or trauma.

The Dorsal Vagal State & Autoimmune Disorders

Individuals frequently trapped in the dorsal vagal state, characterised by learned helplessness or dissociation, experience heightened physiological activity, leading to conditions such as irritable bowel disease and colitis. These cyclical diseases fluctuate between sympathetic and parasympathetic dominance, often defying diagnosis and treatment due to their psychosomatic nature. However, these conditions are better understood as neurosomatic, arising from abnormal brain function.

The connection between HPA hyperactivation (heightened stress response) and dysregulation (hypercortisolaemia, adrenal insufficiencies) and the digestive tract is well understood. Chronic activation of the HPA axis dysregulates digestive capabilities and detoxification, impacting waste elimination. Because the body cannot spare any energy for secondary systems (the focus is solely on survival and nothing else), immunity and digestive capacities are suppressed. As a result, the body secretes less saliva, less hydrochloride (stomach) acid and fewer enzymes, making it difficult for the digestive tract to break down food and assimilate nutrients. Undigested food entering the intestinal tract may ferment adding discomfort (bloating, gas, etc.), irritating the gut lining and affecting its integrity and the fragile balance of the gut microbiome, leading to a net reduction in the production of short-chain fatty acids and greater production of pro-inflammatory markers, including endotoxins, alcohol, histamine and many more. This has severe consequences on the integrity of the gut lining and plays a key role in increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut” syndrome.

When antigens, let they be bacterial components, allergens, larger protein molecules (from maldigested foods), parasites and more, cross into the bloodstream they can wreak havoc just about anywhere in the body (often the weakest system/organ in the body), participating in inflammatory disorders and even autoimmunity. For example, there is a strong correlation between gluten hypersensitivity and autoimmune thyroid disorder (molecular mimicry). There are many more associations linked by a myriad of studies.

The list is not exhaustive…

Key Components of Effective Treatment

Tolerance Building:

Effective trauma treatment involves helping individuals develop the capacity to tolerate and manage overwhelming emotions and physical sensations. Many trauma survivors struggle with alexithymia, which makes it difficult for them to identify and interpret their feelings. This disconnect from their emotions often leads to disconnect from themselves and others.

Through therapy, individuals can learn strategies to increase their emotional awareness and develop healthier ways of coping with distressing feelings. By building tolerance for their emotions, trauma survivors can gradually regain a sense of control over their internal experiences.

Arousal Regulation:

Trauma often dysregulates the body's stress response systems, leading to heightened arousal levels and difficulty in self-regulation. Effective treatment focuses on helping individuals regulate their arousal levels to prevent them from becoming overwhelmed by their emotions. This may involve teaching relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing exercises or progressive muscle relaxation, to help individuals calm their nervous systems. By learning to modulate their arousal levels, trauma survivors can reduce the frequency and intensity of distressing symptoms like anxiety and hypervigilance.

Action Engagement:

Following experiences of physical helplessness, trauma survivors may feel a sense of powerlessness and resignation. Effective treatment empowers individuals to take proactive steps towards healing and recovery. This may involve encouraging them to engage in activities that promote a sense of agency and mastery, such as assertiveness training or participation in meaningful hobbies and interests. By reclaiming a sense of control over their lives, trauma survivors can rebuild their confidence and resilience in the face of adversity.

Importance of Interoception

Understanding bodily signals is essential for trauma survivors to reconnect with their physical selves and navigate their internal experiences more effectively. Interoception, or the awareness of internal bodily sensations, provides valuable information about one's emotional state and physiological arousal levels. Through mindfulness practices and somatic techniques, individuals can learn to attune to their bodily signals and respond to them in adaptive ways. By cultivating a deeper awareness of their internal experiences, trauma survivors can develop greater self-understanding and self-regulation, laying the foundation for healing and growth.

Effective trauma treatment often requires a holistic approach that addresses the interconnected physical, emotional, and psychological aspects of the condition. Here's an overview of the treatment strategies commonly employed in trauma recovery:

Psychotherapy:

Various forms of psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), and somatic experiencing, are often used to help individuals process traumatic experiences, manage symptoms, and develop coping strategies. These therapies aim to address distorted thought patterns, emotional dysregulation, and physiological responses associated with trauma.

Mindfulness and relaxation techniques:

Practices such as mindfulness meditation, deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, and yoga can help individuals cultivate present-moment awareness, reduce physiological arousal, and promote relaxation. These techniques enhance self-regulation skills and provide tools for managing stress and anxiety.

These practices often require no equipment and are free, therefore, they can be used (and abused) at any time being present and taking back control of emotions is necessary. They can also be done very discreetly around others (think breathing exercises or progressive muscle relaxation). It will also dampen the noise around you if it is triggering you.

Body-oriented therapies:

Body-based approaches such as massage therapy, acupuncture, and sensory integration techniques focus on addressing the physical manifestations of trauma stored in the body. These therapies aim to release tension, promote relaxation, and restore balance to the autonomic nervous system, which may be dysregulated following trauma.

Nowadays, many devices are available to help you release muscle tension, such as portable massagers or massaging guns, which have many settings to help work on the exact muscle you want to relax.

Social support and connection:

Building strong social support networks and fostering meaningful connections with others can play a crucial role in trauma recovery. Supportive relationships provide validation, empathy, and understanding, reducing feelings of isolation and promoting feelings of safety and belonging.

Looking at joining support groups may also provide a strong support network of people having experienced similar events and dealing with their own trauma.

Volunteering may also equip you with a newfound purpose and give you responsibilities and pride by helping others, helping you to find new ways to deal with your trauma and responses to triggers.

Lifestyle modifications:

Adopting healthy lifestyle habits, such as regular exercise, balanced nutrition, adequate sleep, and stress management practices, can support overall well-being and resilience in the face of trauma. Engaging in activities promoting physical health and emotional well-being contributes to empowerment and control over one's life.

Trauma-informed care:

Creating a safe and supportive environment that acknowledges the impact of trauma and prioritises individual autonomy, choice, and empowerment is essential in trauma treatment. Trauma-informed approaches emphasise collaboration, transparency, and cultural sensitivity in addressing the unique needs and experiences of trauma survivors.

By integrating these comprehensive treatment approaches, individuals can embark on a journey of healing, reclaiming agency, and rebuilding their lives after trauma. It's important to tailor treatment interventions to the specific needs and preferences of each individual and to recognize that trauma recovery is a gradual and nonlinear process that requires patience, compassion, and perseverance.

Conclusion

Interoceptive, body-oriented therapies play a crucial role in addressing core clinical issues in PTSD, allowing individuals to experience the present without being overwhelmed by past sensations and emotions. By focusing on physical self-awareness and self-regulation, therapy can facilitate a deeper understanding of internal experiences and empower individuals to engage more effectively with their surroundings, fostering mastery and pleasure in life.