Hormone Disruption: The Role of Chronic Stress

Understanding the Foundations — Stress and Hormonal Disruption

An intricate physiological response, stress is a fundamental aspect of the human experience. Stress is the body's reaction to any demand or challenge, which can impact our basic human needs, such as shelter and access to food and water, or how we experience our environment: overexposure to information and electromagnetic fields (radiation, or EMFs), overwhelming demands (work, relationships, rising cost of living, and living in highly-polluted cities), and poorly nutritious ultra-processed food products (known to damage the fragile gut ecosystem).

When stress becomes chronic, a complex cascade of physiological responses unfolds, significantly impacting overall health. Chronic stress — defined by persistent challenges that exceed your ability to cope — not only affects mental well-being but emerges as a potent disruptor of hormonal balance.

The Biology of Stress: A Brief Overview

At its core, stress triggers the release of stress hormones, primarily epinephrine and norepinephrine (or adrenaline and noradrenaline, respectively). If stressors are not removed, it triggers the long-term stress response and the release of cortisol. This hormonal surge prepares the body for a "fight or flight" response, mobilising energy and resources to tackle the perceived threat. While this acute stress response is adaptive, chronic exposure to stressors can lead to dysregulation, initiating a series of detrimental effects on the endocrine system.

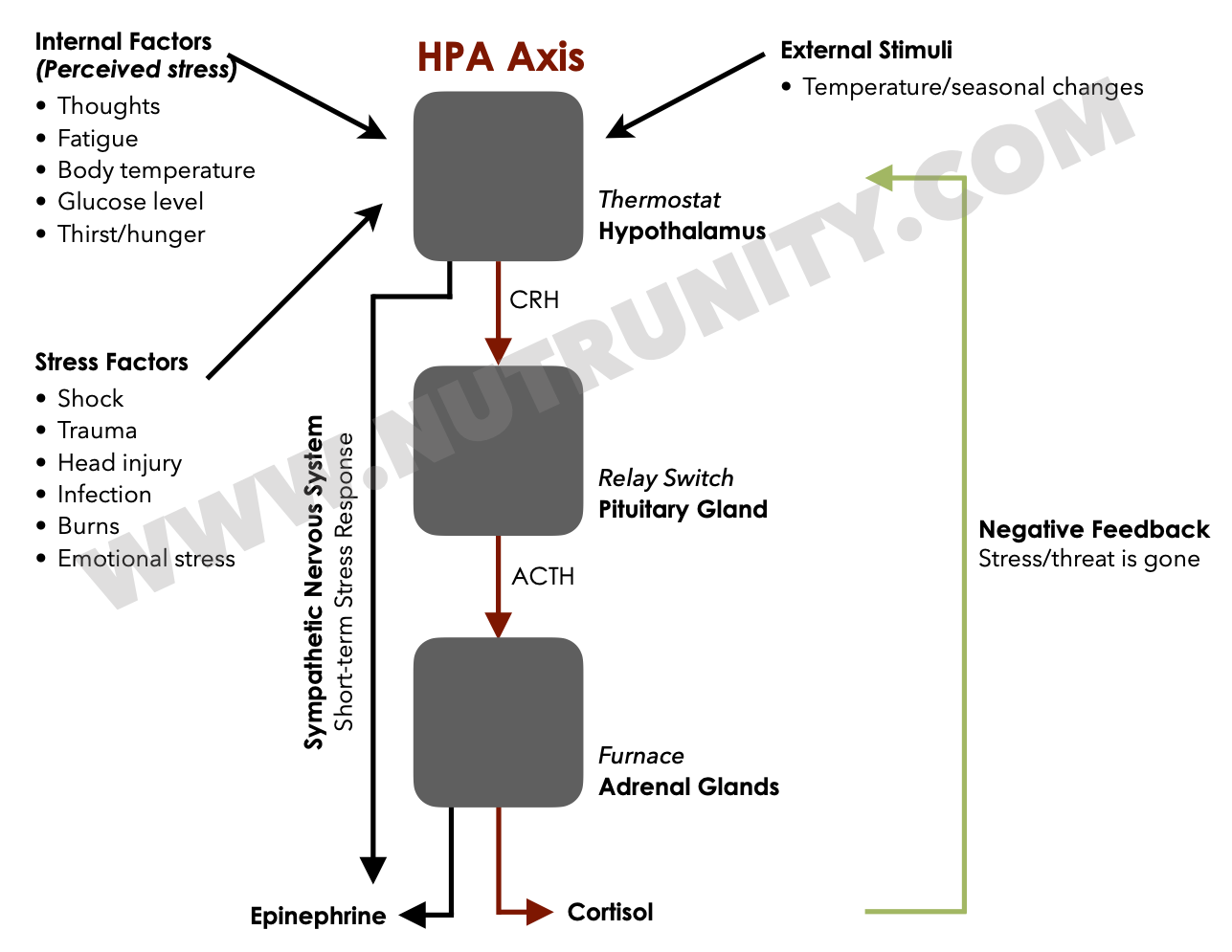

HPA axis and the short-term stress response

The Vicious Cycle of Chronic Stress and Hormonal Dysregulation

A tsunami of studies has demonstrated the intricate relationship between chronic stress and hormonal dysregulation. Prolonged exposure to stressors disrupts the delicate balance of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. (see the above illustration)

The stress response should switch off as soon as the stressors are removed and the elevated concentration of cortisol in the blood has served its purpose (negative feedback); however, when the stressors continue to have an effect (think childhood unresolved trauma, or anxiety: stress that is made up).

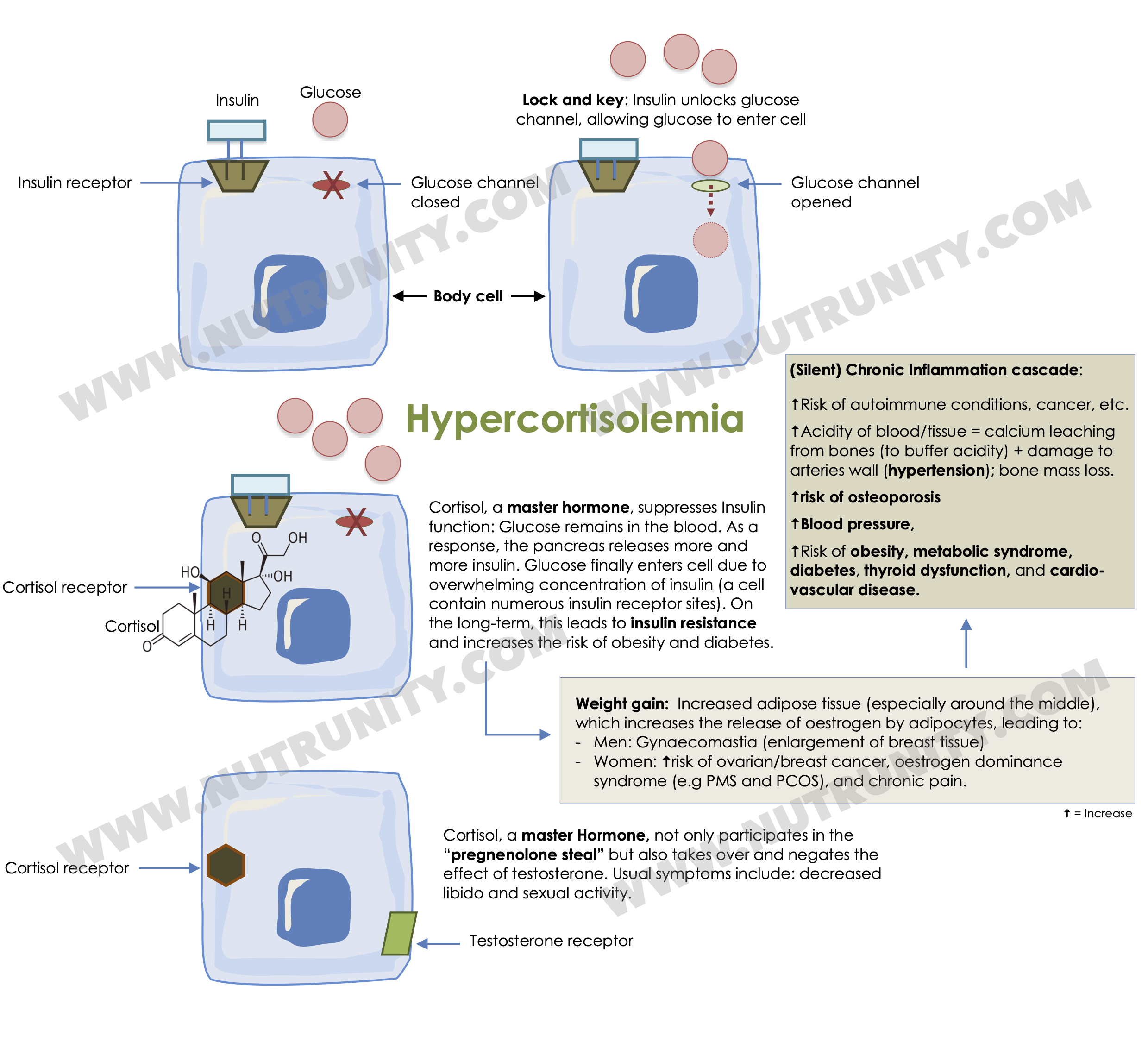

Dysregulation of the HPA axis not only perpetuates chronic stress but also influences the production, release, and processing of various hormones, creating a vicious cycle with far-reaching implications for overall health. This is, in part, due to the dominant effect of cortisol on ALL other hormones and is known as hypercortisolaemia, eventually leading to Cushing Syndrome.

Hypercortisolemia, signs and symptoms, and associated disorders.

Hormonal Impact on the Body

Chronic stress-induced hormonal dysregulation extends its influence beyond the adrenal glands. Studies demonstrate that stress hormones, particularly cortisol, can affect sex hormone production, thyroid function, and even the intricate pathways involved in mood regulation. This is discussed in much detail in “Energise - 30 Days to Vitality.”

1. Physical Manifestations of Chronic Stress

Beyond the psychological toll, chronic stress manifests physically, impacting vital organs and systems. The cardiovascular system, immune response, and metabolic processes all fall under the sway of chronic stress. This may explain why digestion problems, brain fog and low mood are consequences of chronic stress: You cannot ever seem to control your energy levels and favour highly caloric foods and stimulants, such as caffeine and sugar.

2. Stress, Hormones, and Our Modern Lifestyles

The prevalence of chronic stress is intricately woven into the fabric of modern lifestyles. In the U.S. over 75% of all visits to doctors are linked to chronic stress, and about 1,000 patients a day in the UK. We have reached a crisis point, and we appear to be less able to cope with the challenges of day-to-day life.

Scientific investigations shed light on how societal, environmental, and personal factors contribute to this issue. Understanding the complex interplay between stress, hormones, and modern lifestyles is essential for devising effective interventions and embracing a holistic approach to restore hormonal balance and promote well-being.

Hormones play a pivotal role in shaping an individual's mental, physical, and emotional well-being. When these chemical messengers are thrown off balance, profound imbalances can manifest throughout the body.

Source: Guilliams, TG. Edwards, L. (2010).

Section 1: Hormonal Disruption and Lifestyle Factors

Understanding Hormonal Influence on the Brain

Hormones influence every facet of an individual's well-being, affecting mental, physical, and emotional health. These biochemical signals regulate processes as diverse as metabolism, growth, reproduction, and stress response. For example, thyroid hormones govern metabolism and sex hormones play a key role in reproduction. Other hormones regulate bone density and mass, while others support brain plasticity (the creation of new neural pathways).

When hormonal regulation is disrupted, the repercussions reverberate throughout the body, from disruptions in sleep patterns to alterations in mood and cognitive function.

Lifestyle Factors as Disruptors

Beyond genetic predispositions, lifestyle factors can significantly disrupt hormone balance. Nutrition, exposure to air pollution, and chronic stress emerge as key disruptors.

Scientific studies have exposed the intricate relationship between dietary choices and hormonal regulation. For instance, certain dietary patterns, rich in refined sugars and ultra-processed food products, have been linked to disruptions in insulin sensitivity and elevated levels of insulin — a hormone central to metabolism. Conversely, nutrient-dense diets, abundant in antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, and essential vitamins, have shown potential to support hormonal balance.

The air we breathe is now recognised as a dynamic player in hormonal regulation. Research exposes the impact of air pollution on endocrine-disrupting chemicals, with potential consequences for hormone synthesis, release, and receptor binding. From industrial emissions to traffic-related pollutants, and indoor pollution, our exposure is ever-increasing as more and more everlasting compounds are released into the atmosphere — the air we breathe.

Contrary to disruption, evidence suggests that lifestyle factors can be harnessed to reverse hormonal imbalances. It starts with daily exercise, proper nutrition, and mindfulness (including stress-relief modalities, such as gratefulness, journalling, and meditation).

Section 2: The Dominance of Adrenal Hormones

Stress hormones and Hormonal disruption

Scientific perspectives highlight the pivotal role of stress in hormonal balance. Stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, signalling the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands. This stress-induced hormonal surge, while adaptive in acute situations, becomes a double-edged sword in chronic scenarios.

Prolonged exposure to stressors perpetuates a heightened cortisol state, contributing to the dysregulation of other hormones. Under normal circumstances, the body maintains a delicate balance through feedback loops (see illustration above). The hypothalamus and pituitary gland release hormones that signal the adrenal glands to adjust cortisol production based on the body's needs. Chronic stress disrupts these feedback mechanisms, creating a dysfunctional loop where the usual regulatory signals are overridden, and cortisol production remains persistently elevated — affecting most pathways in the body. Because your body is on high alert, the only thing that matters is survival, nothing else.

It is not surprising that the implications of chronic stress-induced cortisol dominance extend far beyond the immediate stress response. Elevated cortisol levels over an extended period have been linked to health issues, including immune suppression, digestive problems, metabolic disturbances, and disruptions in reproductive function.

A holistic Approach

Stress evaluation and management strategies are explored as low-harm, high-benefit interventions, and should be implemented as soon as possible and relied upon as often as possible. Stress management modalities must be employed daily and become automatisms to increase your resilience and improve your quality of life.

Physical Activity

Physical activity emerges as a lifestyle factor with multifaceted benefits. Beyond its well-known impact on physical health, it plays a crucial role in decreasing stress levels and favours the producing feel-good mood boosters like endorphins.

Do not underestimate the power of walking and forest bathing. For individuals unable to engage in vigorous exercise, regular walking is a practical and effective intervention. It is also recommended to help you reconnect with yourself, and so yourself, and to improve your overall quality of life.

Stress-Reducing Techniques

Stress-reducing techniques such as meditation and massage offer promising avenues for hormonal balance. A thorough review of studies has exposed the significant reduction in cortisol levels and a simultaneous increase in mood-boosting hormones like serotonin and dopamine through massage therapy. There are also a multitude of modalities like tapping (EFT), breathwork, journalling, affirmations, mindfulness, meditative yoga, stretching, and more. Some of these techniques may not work for you, so choose what you feel more comfortable with. For example, if you can’t manage to sit still or focus, you may feel unable to reap the benefits of meditating.

Meditation

Mind-body interventions, particularly meditation, stand out as potent tools for addressing chronic stress at its roots. Scientific studies consistently demonstrate the efficacy of meditation in reducing cortisol levels and promoting a state of physiological relaxation. The practice of mindfulness and focused breathing not only counteracts the persistent stress response but also plays a key role in increasing your resilience, empowering you to face stressors with a more adaptive mindset.

To help you start, we have developed “5-minute SOS meditation sessions.”

Nutritional Support

Nutrition plays a pivotal role in supporting the body's resilience to stress. Certain foods and dietary patterns have been linked to improved mood and hormonal balance. Incorporating a balanced diet rich in antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, and stress-modulating nutrients provides a foundation for a resilient body that can better cope with the demands of chronic stress.

The key is to concentrate on blood sugar balancing. Therefore, it is crucial to be mindful of your intake of sugar and stimulants like caffeine, the timing of meals, the quantity of foods, and the choice of foods (think veggies, lean or plant proteins, healthy fats, and less carbs).

Social Connection: Building Resilience Through Relationships

The profound impact of social connections on mental health and stress resilience cannot be overstated. Meaningful relationships and a strong support system act as buffers against the detrimental effects of chronic stress. Engaging in social activities, fostering connections, and seeking support contribute to a holistic approach that addresses the emotional toll of stress.

Social isolation is a stressor (you are disconnected from the world around you and lose the beneficial health effect of being part of a community) but can also result from unrelenting stress (and anxiety disorders).

Restoring the Body's Circadian Rhythms

Much easier said than done; however, it is extremely powerful and should often be the first factor to address when chronic stress becomes a problem. Adequate and restful sleep is a cornerstone of stress management and hormonal balance. Chronic stress often disrupts sleep patterns, creating a feedback loop where inadequate sleep exacerbates stress, and vice versa. Establishing consistent sleep hygiene practices, such as a regular sleep schedule and a calming bedtime routine, becomes crucial in restoring the body's vital rhythms and promoting overall well-being.

References:

Chen, PJ. Chou, CC. Yang, L. et al. (2017). Effects of aromatherapy massage on pregnant women’s stress and immune function: a longitudinal, prospective, randomized controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 23(10), pp. 778-786. doi:1089/acm.2016.0426

Dada, T. Mittal, D. Mohanty, K. et al. (2018). Mindfulness meditation reduces intraocular pressure, lowers stress biomarkers and modulates gene expression in glaucoma: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Glaucoma. 27(12), pp. 1061-1067. doi:1097/IJG.0000000000001088

Del Río, JP. Alliende, MI. Molina, N. et al. (2018). Steroid hormones and their action in women’s brains: The importance of hormonal balance. Frontiers in Public Health. 6:141. doi:3389/fpubh.2018.00141

Fan, Y. Tang, YY. Posner, MI. (2014). Cortisol level modulated by integrative meditation in a dose-dependent fashion. Stress Health. 30(1), pp. 65-70. doi:1002/smi.2497

Field, T. Hernandez-Reif, M. Diego, M. et al. (2005). Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Internation Journal of Neuroscience. 115(10), pp. 1397-1413. doi:1080/00207450590956459

Guilliams, TG. Edwards, L. (2010). Chronic stress and the HPA Axis: Clinical assessment and therapeutic considerations. The Standard. 9(2). Available at: https://www.pointinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/standard_v_9.2_hpa_axis.pdf

Hirokawa, K. Taniguchi, T. Fujii, Y. et al. (2012). Job demands as a potential modifier of the association between testosterone deficiency and andropause symptoms in Japanese middle-aged workers: A cross-sectional study. 73(3), pp. 225-229. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.07.006

Jain, RB. (2014). Thyroid function and serum copper, selenium, and zinc in general U.S. population. Biological Trace Element Research. 159(1-3), pp. 87-98. doi:1007/s12011-014-9992-9

Köhrle, J. (2015). Selenium and the thyroid. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity. 22(5), pp. 392-401. doi:1097/MED.0000000000000190

Kyrou, I. Tsigos, C. (2008). Chronic stress, visceral obesity and gonadal dysfunction. Hormones (Athens). 7(4), pp. 287-293. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1209

Li, H. Cai, J. Chen, R. et al. (2017). Particulate matter exposure and stress hormone levels: A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of air purification. Circulation. 136(7), pp. 618-627. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026796

Matsuzaki, K. Uemura, H. Yasui, T. (2014). Associations of menopausal symptoms with job-related stress factors in nurses in Japan. 79(1), pp. 77-85. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.06.007

McCabe, D. Lisy, K. Lockwood, C. et al. (2017). The impact of essential fatty acid, B vitamins, vitamin C, magnesium and zinc supplementation on stress levels in women: A systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 15(2), pp. 402-453. doi:11124/JBISRIR-2016-002965

Neeck, G. Riedel, W. (1994). Neuromediator and hormonal perturbations in fibromyalgia syndrome: Results of chronic stress? Baillière's Clinical Rheumatology. 8(4), pp. 763-775. doi:10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80047-0

Pedersen, BK. (2019). Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 15(7), pp. 383-392. doi:1038/s41574-019-0174-x

Pervanidou, P. Chrousos, GP. (2011). Stress and obesity/metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 6(Suppl 1), pp. 21-28. doi:10.3109/17477166.2011.615996

Pimenta, F. Leal, I. Maroco, J. et al. (2012). Menopausal symptoms: Do life events predict severity of symptoms in peri- and post-menopause? 72(4), pp. 324-331. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.04.006

Ranabir, S. Reetu, K. (2011). Stress and hormones. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 15(1), pp. 18-22. doi:4103/2230-8210.77573

Sato, K. Iemitsu, M. Matsutani, K. et al. (2014). Resistance training restores muscle sex steroid hormone steroidogenesis in older men. FASEB Journal. 28(4), pp. 1891-1897. doi:1096/fj.13-245480

Seo, DI. Jun, TW. Park, KS. et al. (2010). 12 weeks of combined exercise is better than aerobic exercise for increasing growth hormone in middle-aged women. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. 20(1), pp. 21-26. doi:1123/ijsnem.20.1.21

Vankim, NA. Nelson, TF. (2013). Vigorous physical activity, mental health, perceived stress, and socializing among college students. American Journal of Health Promotion. 28(1), pp. 7-15. doi:4278/ajhp.111101-QUAN-395

Vita, R. Lapa, D. Trimarchi, F. et al. (2015). Stress triggers the onset and the recurrences of hyperthyroidism in patients with Graves’ disease. Endocrine. 48(1), pp. 254-263. doi:1007/s12020-014-0289-8

Yamada, M. Nishiguchi, S. Fukutani, N. et al. (2015). Mail-based intervention for sarcopenia prevention increased anabolic hormone and skeletal muscle mass in community-dwelling Japanese older adults: The INE (Intervention by Nutrition and Exercise) study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 16(8), pp. 654-660. doi:1016/j.jamda.2015.02.017